Earth Law Center Blog

The Global Plastics Treaty and "Plastics Justice"—A Primer

Led by Ocean Program Director Rachel Bustamante, Earth Law Center (ELC) recently released a report entitled “Advancing Ocean Justice in the Global Plastics Treaty.” You can find more information, including links to the full report and a related press release, on ELC’s Ocean Plastics webpage. In this blog post, we break down some key terms and concepts related to plastic pollution, the Global Plastics Treaty, and plastics justice, ending with ways that anyone can get involved in this critically important issue.

Led by Ocean Program Director Rachel Bustamante, Earth Law Center (ELC) recently released a report entitled “Advancing Ocean Justice in the Global Plastics Treaty.” You can find more information, including links to the full report and a related press release, on ELC’s Ocean Plastics webpage.

In this blog post, we break down some key terms and concepts related to plastic pollution, the Global Plastics Treaty, and plastics justice, ending with ways that anyone can get involved in this critically important issue.

What is the Global Plastics Treaty?

The Global Plastics Treaty (GPT) is an international agreement currently being negotiated at the United Nations (UN), with the treaty process having been launched in March 2022 by a resolution of the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA). Its Resolution 5/14 calls for the development of “an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment, . . . which could include both binding and voluntary approaches, based on a comprehensive approach that addresses the full life cycle of plastic.”

This treaty process represents an unprecedented opportunity to address the plastic crisis.

What is the scope of the plastic pollution crisis?

Plastic pollution is severe and widespread. Across their full life cycle (production, distribution, use, and waste), plastics cause damage to people and Nature. For instance, 99% of plastics are made from fossil fuel-based polymers and require greenhouse gas emissions in their production. Then, plastics result in further emissions as they are trucked or shipped to industries and consumers.

Plastics contain harmful chemicals, including known cancer-causing agents (carcinogens), and plastic waste pollutes the environment and can be harmful or deadly to wildlife that ingests plastics or gets tangled in them. Plastic pollution occurs both at the macro-level, such as plastic bags blowing around a city block or discarded fishing nets floating in a river or ocean, and also at the level of microplastics. These tiny plastic particles are now so widespread they have been found in everything from remote alpine raindrops to the bloodstreams of wildlife to a rising percentage of human placentas.

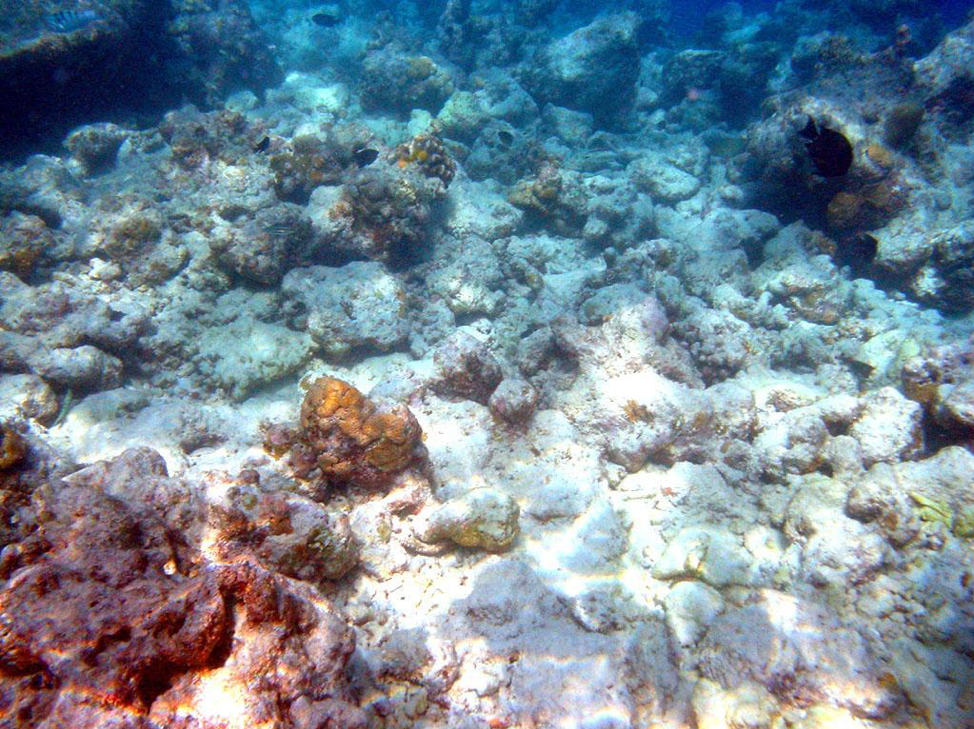

Microplastics have also been found in every ocean basin, and plastics represent a particular threat to ocean life and ecosystems. For a more in-depth take on the research and details of this issue, we suggest reading “An Earth Law Solution to Ocean Plastic Pollution” by Michelle Bender. “Plastic fragments can transport contaminants, increase their environmental persistence, and concentrate organic pollutants up to 106 times that of surrounding seawater,” she writes. “The chemicals present in plastic pollution, such as PCBs, lead to reproductive disorders or death, increase the risk of diseases, and alter hormone levels.”

While plastics impact virtually every ecosystem and human being, it is clear that disproportionate negative impacts occur to the ocean and across race, occupation, ethnicity, class, gender, and age—which leads us to the topic of plastic justice.

What is plastic justice?

The term “plastic justice” points to the reality that the harms caused by the full life cycle of plastics disproportionately impact the ocean and marginalized communities, and so a just response requires attending to those disproportionate impacts.

To take one example: enormous amounts of plastic are dumped into the ocean every year. These plastics not only harm and kill fish and other sea life but also wash up on the shores of island and coastal states, such that impoverished communities suffer the health and economic consequences of plastics they neither produced nor used.

Plastic justice is comprised of three main elements:

the protection of the ocean

the fulfillment of human rights

the progression of social equity

ELC’s report introduces plastic justice in much more detail and maps the communities most burdened by plastic pollution, including Small Island Developing States, Indigenous Peoples, People of Color, the Global South, youth, and other marginalized communities.

How is the Global Plastics Treaty being negotiated?

More than 160 countries participate in the process, which is being overseen by a body called the International Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution (INC). The development of a draft treaty takes place through a process of comment and revision, punctuated by multiple rounds of in-person negotiation.

Three rounds of negotiation, held in Uruguay, France, and Kenya, took place in 2022 and 2023. A fourth (INC-4) will take place in Ottawa, Canada from April 23 to 29, 2024. A fifth and likely final round of negotiations (INC-5) is scheduled for November 5 to December 1 in Busan, South Korea, with plans for treaty adoption in 2025.

What is (and isn’t) in the current draft of the Global Plastics Treaty?

As it stands, the treaty text combines a blend of binding and voluntary targets. Following the last session of negotiations (INC-3), substantial diverging views on the scope and ambition of the agreement caused the now Revised Zero Draft to grow almost three times in size, aiming to accommodate all of the inputs of countries. This means that provisions across the six parts, which cover issues including microplastics, addressing existing pollution, preventing new pollution, a just transition, waste management, and implementation, currently include a range of options for countries to discuss at INC-4.

Though some countries have advocated for limiting the scope of the treaty to cover only pollution or waste management, Resolution 5/14 mandates the agreement cover the full life cycle. Currently, there are no provisions to reduce plastic production at a global level or protect against biodiversity impacts, nor are there numerical targets that mandate a specific timeline for implementation.

Although an international treaty on plastic pollution is an important step and much progress has been made toward it, it’s disheartening to see that the current draft lacks a binding obligation for treaty signatories to protect human rights. It lacks even a single instance of the word “justice,” much less a substantive incorporation of justice principles and human rights.

Earth Law Center's Report: Highlighting the Need for Ocean Justice

ELC’s report, “Advancing Ocean Justice in the Global Plastics Treaty,” emphasizes that ocean justice is crucial for achieving an effective agreement. With the next round of negotiations scheduled for April in Ottawa, Canada (INC-4), this report can serve as a vital advocacy tool, highlighting how the full life cycle of plastics disproportionately harms the ocean and marginalized communities and thus demands a response grounded in justice.

The report includes geographical and sectoral survey findings—highlighting, for instance, that support for including human rights in the final treaty was notably strong among African and Latin American countries, and that large majorities of surveyed representatives of government, nonprofit organizations, academia, and business support using Rights of Nature principles to help guide the treaty. Other recommended principles of law include Indigenous Knowledge, polluter pays, intergenerational equity, and common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities.

“The importance of embedding justice within this treaty cannot be overstated,” said Rachel Bustamante, Ocean Program Director at ELC. “The plastic life cycle jeopardizes every Sustainable Development Goal, contributes significantly to global climate change, and threatens human rights worldwide. How equitable and just this treaty turns out to be will have undeniable implications for people, the ocean, and truly, the planet.”

What is #Youth4PlasticJustice?

To build continued support and momentum for a Global Plastic Treaty that includes consideration for ocean justice and human rights, Earth Law Center, EarthEcho International, The Ocean Project, and World Ocean Day are planning a series of actions as part of an advocacy campaign called #Youth4PlasticJustice at INC-4, taking place from April 23 to 29, 2024 in Ottawa, Canada.

How can I get involved?

Join the #Youth4PlasticJustice movement:

Raise your voice by helping contribute to a video with a call-out to world leaders at INC-4 to support the inclusion of justice and human rights in the Global Plastics Treaty. Check out these submission details and RECORD AND SUBMIT YOUR VIDEO HERE.

Sign the petitions to demand negotiators advance ocean justice at INC-4 and adopt a strong Global Plastics Treaty.

Follow Earth Law Center, EarthEcho International, and World Ocean Day on social media to learn more and stay up to date on actions.

Ocean Optimism Making Waves

June 8th marks World Ocean Day, a worldwide call to action to put the Ocean first. In the 15 years since its official recognition by the United Nations, this designation has grown into a global movement, uniting youth leaders, policymakers, Indigenous communities, scientists, and a vast range of both private sector and civil society organizations to protect and restore the Ocean.

This World Ocean Day presents an opportune moment for genuine reflection, allowing us to consider both the challenges confronting the Ocean and to embrace optimism for the future. Today, we reflect on the recent victories of Earth Law Center’s Ocean Rights program and how we can further catalyze action to change the tides on Ocean health.

The Ocean Race One Blue Voice Pavilion in Newport, Rhode Island, May, 2023. Photo by Rachel Bustamante

Ocean Rights Gains Momentum

The initiative “Towards a Universal Declaration of Ocean Rights (UDOR)” is gaining remarkable momentum! Launched in March 2022 with The Ocean Race, Nature’s Rights and the municipality of Genoa, Italy, the UDOR aims to create a shared global vision of positive human-Ocean relationships and give the Ocean a voice and representation within a multinational governance system.

The government of Cabo Verde signed on in 2022 to lead the introduction of Ocean Rights within the United Nations General Assembly in September 2023, and with the support of Monaco, are leading discussions with governments to increase formal support at the UN and national levels. Additionally, local governments have also formally supported the UDOR, including Itajaí and Santa Catarina, Brasil, Aarhus, Denmark, and Newport as well as the House of Representatives of Rhode Island.

The campaign has fostered dialogue and consultation through six 'Innovation Workshops' thus far, bringing together over 150+ experts, policymakers, business leaders, lawyers, Indigenous Peoples, scientists, NGOs, and stakeholders to engage in meaningful discussions on Ocean Rights. We are now in the process of taking all the input into account and moving towards a draft document outlining a new values-based foundation (or code of conduct) to serve as a starting point for the UDOR and its inclusion in upcoming UN agendas.

In addition, the One Blue Voice petition to collect support has now garnered over 24,000 signatures. We encourage you to actively participate in shaping an ecologically sustainable future for the Ocean by signing and sharing the petition. Your support is crucial in ensuring the thriving and well-being of the Ocean!

The Universal Declaration of Ocean Rights milestone map.

Panama Recognizes Sea Turtles’ Rights

In March 2023, Panama’s President Laurentino Cortizo signed a national law promoting the Protection and Conservation of Sea Turtles and their Habitats. This law recognizes the rights of sea turtles to live and have free passage in a healthy environment, free of pollution and other human impacts that cause physical damage. Truly a landmark example, this law is likely the first national law to guarantee and identify the rights of a specific species.

Photo by Michael Ryan Clark.

In 2021, Congressman Gabriel Silva proposed the law, which underwent three legal debates to receive input and shape its provisions before ultimately reaching the President's desk. Earth Law Center, in partnership with The Leatherback Project, provided legal feedback to the draft.

This law identifies sea turtles as having individual value beyond the context of human benefits or perceptions, especially given that these highly endangered species offer a window into the health of the Ocean. Occurring in one of the most biodiverse countries on Earth, this law opens the door for other species’ rights to be recognized in Rights of Nature supporting countries, and sets a fantastic precedent for future legislation!

New Publication on Sharks and Rights of Nature

Rachel Bustamante of Earth Law Center recently published Beyond Protection: Recognizing Nature’s Rights to Conserve Sharks, in the journal Sustainability, laying out approaches to improve the protection and restoration of sharks and their habitats. Globally, sharks are highly threatened by overfishing, habitat degradation, and climate change. As both keystone species and apex predators, sharks regulate food webs and maintain ecological balance. In fact, sharks are fundamental to maintaining a healthy Ocean!

This paper explores how we can move beyond merely protecting sharks and reimagine a more harmonious relationship between humans, sharks, and the Ocean. This publication is within an emerging body of work that reimagines how we can use Rights of Nature frameworks to enshrine protections for specific species.

What Can You Do?

These three stories are but a small sliver of our work. Continue your involvement and support of Earth Law Center’s many efforts to ensure the Ocean is healthy and thrives.

In addition, support the World Ocean Day movement directly by taking the Conservation Action Focus survey.

Most importantly, continue to spread the word about the importance of conserving, protecting, and empowering the Ocean!

Graphic by UN World Oceans Day

Exploring the Deep-Seas and the Risk of Mining

ELC Ocean Team, Xander Deanhardt and Kendall Fowler

The deep-sea is a region full of biodiversity. Scientifically defined as the area of the Ocean 200 meters or deeper, the deep-sea is now at risk of exploitation from mining. In June 2021, the island nation, the Republic of Nauru, invoked a two-year rule under the International Seabed Authority (ISA), the United Nations body that oversees mining. This action pressures the ISA to complete regulations so that commercial mining of the seabed, a process where machines scour the seafloor for rare minerals, could begin as early as mid-2023. Consequently, if applications from industries wanting to mine the seafloor are submitted, this two-year rule means they could be considered by the ISA even without final guidelines in place to protect the marine environment.

Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2017.

This issue however is not one solely of industry versus environmental proponents. The mineral modules present on the deep-sea floor are rare minerals argued as necessary for the construction of electric vehicle batteries. Some argue that in order to curb greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere and transition the global economy to more sustainable transportation, mining of the deep-sea is required. However, more studies are emerging showing that deep sea minerals will not be necessary by 2050 and car manufacturers such as Volkswagen and BMW, have voiced they will not be using these minerals in their supply chain.

How is DSM being regulated?

The ISA was established under the UN Convention on the Laws of the Sea (UNCLOS) and has a mandate to regulate and control all mineral related activities in the international seabed and subsoil, known as the “Area” and outside the jurisdiction of any single nation. The ISA is responsible for creating regulations to guide decision making in the Area. Under the ISA’s mandate from the UN, it must act on behalf of all mankind and take necessary measures to ensure effective protection of the marine environment. The ISA has allowed regulated exploration of the Area, facilitating scientific research to guide a better understanding of the deep-sea environment, and has been developing regulations for exploitation for a few years. In September 2022, the ISA announced that the company, Nauru Ocean Resources Inc (NORI, a Republic of Nauru national), was given permission to “test-mine” in the Clarion Clipperton Zone. NORI is projected to remove 3,600 tonnes of polymetallic nodules (the equivalent of the weight of approximately 35,000 blue whales) by the end of 2022.

UNCLOS states that if a nation alerts the ISA that it has the intent to start exploitation of the Area, a two-year deadline is triggered, giving the ISA two-years to complete regulations for exploitation before applications for mining can be submitted. The Republic of Nauru sent a request to the ISA in June of 2021 and due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the complexity of the issue, the regulations are not near completion despite the deadline of the two-year trigger occurring in the summer of 2023. If the regulations are not complete by the July 2023 deadline, contractors could start to submit plans of work for mining the deep-seabed and permits may be issued based on only provisional exploitation regulations.

Why is deep sea mining an important issue?

The Ocean is the lifesource of our planet, providing half of the oxygen we breathe, sequestering carbon dioxide and mitigating climate change, and providing jobs, food and livelihood for millions of people. The deep sea has flourished for millenia, supporting some of the most biodiverse and scientifically important ecosystems on Earth, and is vital to the overall health and functioning of the Ocean. Many deep-sea organisms have long life cycles, for example there are sponges found to be 10,000 years old! Little is known regarding deep-sea ecosystems and mining impacts to the deep-sea and Ocean as a whole. However, novel research analyzing the potential harms of mining suggests devastating effects. In fact, initial studies have indicated that the effects of deep-seabed mining on the seafloor could persist for hundreds of years. Other projections suggest that each individual mining operation may disturb between 300 and 800 square kilometers per year, with impacts spreading over an area two to five times larger due to sediment being kicked up by mining machinery. An additional harm would be the noise produced by a deep-sea mine. Studies have estimated that a single deep-sea mine’s noise could travel approximately 500 kilometers, causing disturbances and confusion for several deep-sea creatures.

As noted by the Pacific Blue Line Initiative and others, for millennia, communities and peoples worldwide have revered the Ocean as a living being, and as an ancestor or kin, with whom we have responsibilities to respect and care for. In fact, the Hawaiian creation chant, or Kumulipo, explains how life began from the first organism, a coral polyp found in the deep sea, and is the extension of our genealogy.

Additionally, over 90% of Pacific people rely on the Ocean for their livelihood. Negative impacts on fish in or near the area will be felt by those inhabiting coastal communities. A report by the Deep Sea Mining Campaign and MiningWatch Canada stated that DSM would have negative repercussions for Pacific Islanders, specifically, it would have negative impacts on local fishers which are a main source of wealth, food security, and employment for many in the Pacific. DSM will therefore result in environmental degradation and destruction of livelihoods and habitats across the Pacific and world.

Image credit: Amanda Dillon, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2011914117

What can you do?

While some countries and industries push to mine for the minerals needed for electric vehicle batteries from the seafloor, the future of deep-sea mining is still uncertain, and there are many parties trying to shape its future. Several countries, NGOs, marine scientists and policy experts are calling for a moratorium, or ban, on deep-sea mining, citing the unknown extent of harm that deep-sea mining could cause to marine and coastal environments and species. Additionally, several member nations of the ISA as well as NGOs are exploring alternative legal options to halt the possibility of mining contracts receiving conditional approval this year in the absence of completed and adopted exploitation regulations. Many arguments are grounded in the idea that the ISA is mandated to protect the marine environment, and the limited information known about mining the deep-seabed indicates possible irreparable damage and widespread effects. The next meeting of the ISA Council is Starting Now, (in March 2023) make sure your voice is heard, such as signing a petition below or writing to your countries delegates.

Call on your government to add its voice and support a global ban or precautionary pause on DSM.

Click the following link to add your name to the official letter to stop deep-sea mining. Signatures from the letter will be delivered to United Nations and International Seabed Authority representatives.

Support and share the Pacific Blue Line Initiative and Indigenous petition against DSM.

Additionally, watch and share Deep Rising, a new documentary that draws attention to the impacts deep-sea mining would have on the environment as well as other well made educational videos, including this one from Deep Sea Conservation Coalition and learn more!

What about the Rights of Nature?

ELC is exploring how alternative legal pathways may support the global call to stop DSM before it starts. Rights of Nature recognizes Nature as a living being with inherent rights, with the underlying philosophy and ethic that all beings have rights and intrinsic worth merely for existing. Over thirty countries have embraced the Rights of Nature through constitutional amendments, national law, judicial decisions, treaty agreements, local law, or resolutions. Scientific evidence that deep-sea mining will likely harm if not completely devastated marine environments and species runs completely contrary to Rights of Nature, which is now recognized as an integral part to the implementation of the recent global agreement for biodiversity, known as the Kunming-Montreal Global biodiversity framework. More to come in a second blog on this critical issue, but for now, watch this short video clip discussing the importance of shifting the focus away from the right to use the Earth’s natural resources and toward a Rights of Nature approach.

Get involved and stay up to date on deep-sea mining:

Image courtesy of the NOAA Ocean Exploration, Exploring Deep-sea Habitats off Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Rights for the Southern Resident Orcas Gains Momentum

By Michelle Bender, Rachel Bustamante and Kriss Kevorkian

The Southern Resident Orcas are a critically endangered subspecies of orca found primarily off the coasts of British Columbia and Washington in the Salish Sea. They have been at the center of a campaign led by Earth Law Center (ELC) and partner, Legal Rights for the Salish Sea (LRSS), to protect and recover their population by recognizing their inherent rights and the ecosystems on which they depend. The long-term goal is State level recognition of the population’s inherent rights and active steps towards implementation. The campaign was launched in 2018 as a response to their continued decline, despite federal legal protections for nearly two decades. The Southern Resident Orca (“the Orcas”) has only 73 individuals left in the wild. The original scope focused on the entire Salish Sea, but ELC and LRSS decided to pivot and focus on the Orcas as the stepping stone to a broader paradigm shift in Washington, because as the Orcas go, we go.

In 2019/2020, ELC worked on a draft State bill with various legal experts, and focused on education and awareness building. ELC and LRSS have been busy at work, including holding many workshops and roundtables to increase Rights of Nature education in the Pacific Northwest. ELC also created a toolkit which was distributed early in 2022 to provide advocates with the tools they need to support the campaign; including a template resolution, talking points, frequently asked questions and social media templates. You can take action and view the toolkit here. (We encourage viewing the template resolution as a guide while adding the unique views and values of your community. Please let us know when you've done this so we can include you in the campaign.)

Jefferson County Commissioners alongside members of the North Olympic Orca Pod at the signing of the Jefferson County Proclamation

In late 2022, our initiative started to receive significant support at the local level. It began when Port Townsend expressed interest after outreach from LRSS and ELC drafted an updated version of our template resolution in line with a Proclamation. Since December 2022, four cities (Port Townsend, Gig Harbor, Langley, Bainbridge) and two counties (Jefferson County and San Juan County) in Washington State have passed proclamations recognizing the inherent rights of the Orcas (you can view all the proclamations here), and the number continues to grow.

More cities and counties are also considering proclamations and we will continue to update this blog as they come in! These local actions are creating the momentum needed to call for immediate state-level action to address the main threats to the Southern Resident Orcas’ survival. Local organizing and resolutions/proclamations have proven powerful tools to gain state and federal action in the United States, and we hope that 2024 will be the year for a state bill or comparable proclamation in Washington’s legislative session.

Who are the Southern Resident Orcas?

The Southern Resident Orcas are a keystone species in the Pacific Northwest, meaning they play a critical role in sustaining the ecological health of the ecosystems they inhabit and are an important indicator of Ocean health. The primary threats to Orcas include a limited availability of their primary prey, chinook salmon, underwater noise and toxic contaminants polluting their habitats. They are highly social creatures that are culturally, spiritually, and economically important to the people of Washington State and the world. To explore more about the Southern Resident Orcas and their ecological importance, read more here.

How can recognizing their rights help their dire situation?

Recognition of their inherent rights demonstrates that we value their population and acknowledge their ecological needs. For example, the Port Townsend proclamation states that the Orcas have inherent rights to: “life, autonomy, culture, free and safe passage, adequate food supply from naturally occurring sources, and freedom from conditions causing physical, emotional, or mental harm, including a habitat degraded by noise, pollution, and contamination.” Recognizing the inherent rights of the Orcas is not only crucial for the protection and recovery of their population but also for respecting and upholding the cultural, spiritual, and economic importance of these creatures to the Indigenous communities who have lived in the region for millenia.

Approximately 30 countries already have hundreds of Rights of Nature laws, with dozens at the local and tribal levels in the United States. For example Santa Monica's Sustainability Rights Ordinance, the Nez Perce's resolution recognizing the rights of the Snake River, and both San Francisco and Malibu have passed resolutions protecting the rights of whales and dolphins in their coastal waters.

Take action to help protect the Southern Resident Orcas and their ecosystems!

Overall, this campaign is making significant progress in advocating for safeguarding and recovering their declining population. The support of cities and counties in Washington demonstrate a growing recognition of the urgent need to protect this species and their habitat. However, more action is needed to ensure their long-term survival.

To help protect the Southern Resident Orcas and their ecosystems, you can stay informed and engaged by following the progress of this ongoing campaign, learning more about these magnificent species, and advocating for stronger protections.

Previous blogs on this campaign:

The Ocean needs a High Seas Treaty

Silas Baisch from Unsplash

The Ocean needs a High Seas Treaty

The High Seas are two-thirds of the world’s Ocean. Despite being home to a myriad of biodiversity, (such as the Pacific Blue Tuna, White Shark or Leatherback Sea Turtle), and numerous species still unknown to science, there is still no comprehensive framework on how to govern human activity on the High Seas.

History of High Seas Governance

In 1982, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) marked the beginning of global agreement for the Ocean. The High Seas, also known as the Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (ABNJ), is the water column of the Ocean areas outside a coastal country’s Exclusive Economic Zone, generally 200-miles offshore. That is to say, no one country has the sole responsibility of these areas, so governance ought to be collective and collaborative across the globe.

While UNCLOS requires nations ‘to protect and preserve the marine environment,’ there are significant legal and governance gaps that consequently, have not effectively deterred overfishing and other human induced threats.

Fortunately, there has been recognition of the need to better protect marine biological diversity on the High Seas for decades. The development of a new international and legally-binding treaty under UNCLOS is long overdue, but has yet to reach formal adoption.

High Seas Treaty Talks Continue

The fifth round of United Nations High Seas negotiations (IGC-5) ended in New York on August 26, without reaching consensus on the treaty.

Though IGC-5 was intended to be the last scheduled session, delegations will have to meet again this year to fulfill the deadline of adopting the treaty by the end of 2022 (set by UN General Assembly resolution 72/249).

Commenting on the 2022 target, the High Seas Alliance, a coalition of organizations, of which Earth Law Center is a part of, pushed for momentum and collaboration between States to continue, stating “this is essential if the world is to achieve the goal of protecting 30% of the ocean by 2030 - something which cannot be achieved without the Treaty.”

Why the urgency?

The failure to adopt a treaty to protect marine life on the High Seas comes at a critical time. Speaking at the UN Ocean Conference in Lisbon in June, UN Secretary-General António Guterres declared “we have taken the ocean for granted and today we face what I would call an ocean emergency.”

Ocean health continues to decline. This is a defining moment and historical opportunity to restore a relationship of care and stewardship of the Ocean.

Rights and Interests of Marine Life

Though State interests and disagreements halted the negotiation process, one brightspot is the recommendation submitted by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) for the treaty to include:

“Stressing the need to respect the balance of rights, obligations and interests set out in the Convention, as well as the rights and interests of future generations and marine life to a healthy, productive and resilient ocean” (Preamable Paragraph 2).

Where negotiations ended, this text was not yet included in the treaty, but we look forward to continuing advocacy for the Ocean’s rights and interests to be recognized. This would be the first global treaty to do so!

Acknowledging the Ocean as a rightsholder and interest would help ensure the Ocean’s needs and well-being are considered in decisions that affect the health of marine ecosystems and biodiversity. In practice, this could strengthen implementation of States’ obligations to protect and conserve the High Seas by recognizing that human activity must be governed by and respect the Ocean’s intrinsic value and ecological limits.

Additionally, this would promote and align with many Indigenous peoples worldviews, and provide an avenue for increased participation of Indigenous Peoples as those who may represent the Ocean’s interests and needs in decision making under the new agreement.

Indigenous and local communities have been widely excluded and underrepresented in the treaty process, despite supportive nations calling for their direct inclusion and consultation. Just as many Indigenous and coastal peoples have been teaching for millennia, we are in a deeply connected relationship with the Ocean. The Ocean is our source of life and a living sacred entity. For centuries this kinship understanding has guided activities, balancing between the needs of people and the capacity of Ocean. Amplifying diverse understandings of relating to the Ocean, can not only help replace our focus on exploiting the High Seas, but help guide our use and value of the Ocean.

Ocean Stewardship

We also commend and support Article 5 to remain in the treaty that calls for the stewardship of the High Seas, “protecting, caring for and ensuring responsible use of the marine environment, maintaining the integrity of ocean ecosystems and preserving the inherent value of biodiversity” (Article 5 k.).

The stewardship principle strengthens States’ responsibility to maintain healthy and thriving Ocean ecosystems on behalf of present and future generations of all life. This means helping States’ adhere to the best available scientific evidence and include the Ocean’s needs in decision making.

Rather than fulfilling States’ short-term interests, active stewardship requires prioritizing the long-term well-being of the Ocean. In fact, in 2022, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) produced an assessment report on the valuation of Nature, highlighting that, ‘a broader diversity of nature’s values’ should be incorporated into decision making. It additionally finds that the causes of and solutions for our global environmental challenges are tightly linked to the ways in which we value our environments (p.4).

We urge adoption of a treaty this year that recognizes the inherent value, rights and interests of the High Seas and States’ responsibility to conserve. This will signify a turning point from “business as usual” towards living in harmony with Mother Earth. The Ocean needs us to adopt a global vision and treaty that embodies stewardship, care and respect for Ocean health.

Join ELC in our efforts to encourage governance respect the Ocean’s Rights and interests!

Find Updates on the High Seas Alliance Treaty Tracker

Iceland Announces End to Whaling

By Emma Hynek

In March 2022, Iceland announced an end to the country’s long standing whaling tradition, citing a lack of interest and profit as the reasoning behind the decision. However, once it takes effect in 2024, the impacts will extend far beyond financial. Though not often considered, whales play a critical role in the ocean’s ecosystem, and there is increasing evidence that cetaceans possess high levels of intelligence and sentience. With the end to Iceland’s whale hunting industry nearing, we hope to see further protection and recovery of whale populations.

Whaling History

National Geographic writes that whaling dates back to the 1600s and was a practice that could be found in Iceland, Norway, Japan, and America. Whaling in the United States was banned in 1971, and this year, Iceland announced its plans to allow current whale hunting quotas to expire in 2024, effectively ending the whaling practice in Iceland, and leaving Norway and Japan as the only two countries where whaling is still legal.

BBC reported on Iceland’s decision to ban whaling, saying, "Why should Iceland take the risk of keeping up whaling, which has not brought any economic gain, in order to sell a product for which there is hardly any demand?" Svandis Svavarsdottir wrote on Friday in the Morgunbladid newspaper.”

In 1982, the International Whaling Commission announced a moratorium on whaling, a decision that has helped protect whales to this day. Though whaling still occurs in Norway and Japan, the moratorium allowed previously hunted whale populations to recover, writes National Geographic. In recent years, as a result of increasing evidence of whale intelligence and sentience, many have pushed for further protections and even the recognition of whales as having legal rights.

Why Is Protecting Whales Important?

According to Whale and Dolphin Conservation, “Whales play a vital role in the marine ecosystem where they help provide at least half of the oxygen you breathe, combat climate change, and sustain fish stocks. How do they do it? By providing nutrients to phytoplankton.” These nutrients, specifically iron, nitrogen, and phosphorus, are dispersed through their fecal plumes.

Despite their importance, they still face many threats to their existence. In addition to hunting, “…industrial fishing, ship strikes, pollution, habitat loss, and climate change are creating a hazardous and sometimes fatal obstacle course for the marine species,” states the World Wide Fund for Nature.

Whaling has also caused whale populations to decrease immensely. This World Economic Forum article details the number of whale species that have been reduced to near extinction through whaling. When whale numbers decline, so does the overall health of the ocean. However, the article also reiterates that the IWC’s moratorium helped to bring whale populations to a healthier number, citing the gray whale as an example of the 1986 moratorium’s success. “The moratorium was largely successful, with the population of Western gray whales increasing from 115 individuals in 2004 to 174 in 2015. The WSA humpback whale, which numbered fewer than 1,000 for nearly 40 years, has recovered to close to 25,000, according to the latest study.”

The Helsinki Group, based in Helsinki, Finland, released a declaration in 2010 calling for the rights of cetaceans to be recognized. The Helsinki Group is just one of many organizations that are dedicated to granting rights to cetaceans. The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) has pushed for cetacean rights to be recognized, as have Sonar and ELC.

Next Steps

While there is still work to be done, it is encouraging that a previous ban on whaling created a positive impact. With legal rights for cetaceans not yet in place and whaling set to end in Iceland, now is the time to reinvigorate the fight for the rights of whales and all cetaceans. Earth Law Center has worked for several years to lead initiatives around the world to protect these intelligent, vital creatures, including the Southern Resident Orca campaign, which is a campaign for state recognition of the Southern Resident’s inherent rights to life, which includes the right to life, autonomy, free and safe passage, adequate food supply from naturally occurring sources, and to be free from conditions causing physical, emotional, or mental harm, including a habitat degraded by noise, pollution and contamination.

"If humans are to survive we must re-remember our kinship with Nature and our non-human relatives. This will undoubtedly require changes in the way we do business; opening space for innovations so that we can have a future with clean rivers, ocean and seas, and healthy habitats for humans, animals and plants alike." says Elizabeth Dunne, Director of Legal Advocacy at Earth Law Center.

ELC’s very own Michelle Bender has also written an e-book on Ocean Rights, which can be found here. We urge you to join our mission to protect the rights of the ocean and the creatures it houses!

How You Can Help

· Click here to learn more about ocean rights.

· Click here to donate.

· Click here to join our team as a volunteer!

Advancing Ecocentric Law for Antarctica

Antarctica, the white continent in the Southern Hemisphere known as one of the most pristine places on Earth absorbs nearly three-quarters of global excess heat and captures almost one-third of of the planet’s carbon dioxide.

Not only does Antarctica contain 90% of the ice and 70% of the fresh water on Earth, a host of species live only here including: 5 species of penguins, 6 whale species, 200+ fish species, and 23 mammalian species. Did you know that Emperor Penguins have lived in Antarctica for 60 million years?

Antarctica not only profoundly affects Earth’s climate and ocean systems, its ice sheet bears a unique record of what our planet’s climate was like over the past one million years.

Factors Challenging the Ecosystems of the Antarctic Peninsula

Climate change, however, threatens the iconic Emperor Penguins and indeed most life in this unique ecosystem with extinction.

The Antarctic Peninsula has warmed at a rate about 10 times faster than the global average. The average annual temperature of the Western Peninsula has increased by nearly 3°C in the last 50 years.

Fishing (both legal and illegal), invasive species, tourism, pollution, oil/gas mining and human infrastructure compound the stresses threatening the delicate ecosystems of Antarctica.

Opportunities to Advance Conservation of Antarctica

Many groups and governments have taken up the call to protect Antarctica, including the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition (ASOC). Among their objectives, ASOC advocates for science-based policies within the existing Antarctic governance framework, namely the Antarctic Treaty signed 1959. Now with 50 signatories, the treaty sets aside Antarctica as a scientific preserve and establishes freedom of scientific investigation.

The creation of the Ross Sea Protected Area created in 2017, protects one of the most biodiverse and productive marine areas in the region. At the time this marked the largest MPA in the world, covering 1.55 million square kilometers, of which 1.12 million square kilometers is fully protected. This represents one of the most significant conservation milestones for Antarctica to date.

With no permanent population, all personnel found on Antarctica hail from other countries (mostly ones who have laid claim to Antarctica but also those with no official claim). Many of these do not recognize each other’s claims. All this makes it exceedingly challenging to create and implement the holistic deep protections that Antarctica now urgently needs to safeguard its unique ecosystems.

Earth Law for Antarctica

Earth Law Center has joined a coalition to create a Declaration of Rights of Antarctica to provide a framework for a new eco-centric vision, planned for launch at Earth Day in April 2022.

Building on earlier frameworks to protect oceans and rivers, Earth Law Center has worked to catalyze a global movement to curtail activities which harm diverse ecosystems.

The declaration aims to provide a code of conduct, to manage human activity in Antarctica with the protection of the ecological needs and natural capacities of that unique ecosystem as a priority. Similar to the Universal Declaration on Human Rights and World Charter for Nature, countries can then join in supporting, implementing and enforcing this new norm.

“Antarctica is a ripe opportunity for reimagining governance and reclaiming sovereignty for the natural inhabitants of the area. Rather than seeking to claim parts of the whole, and exercise rights given to us under the Treaty system, we instead would honor our responsibilities to ensure the area is protected as a common heritage for future generations of all life.” Michelle Bender, Ocean Campaigns Director, Earth Law Center.

Take action today and be part of the solution to rebalance the human-Nature relationship:

Get ELC’s ebook about Ocean Rights

Stay informed by signing up for ELC’s monthly newsletter

Join our newly launched ELC Ambassador Community as a moderator here

Make a monthly contribution of $5 to protect our only home

Earth Law Center Partners with The Leatherback Project to Support Sea Turtle Conservation Efforts in Panama

By Emma Hynek

Panama Introduces New Conservation Law to Protect Endangered Sea Turtles

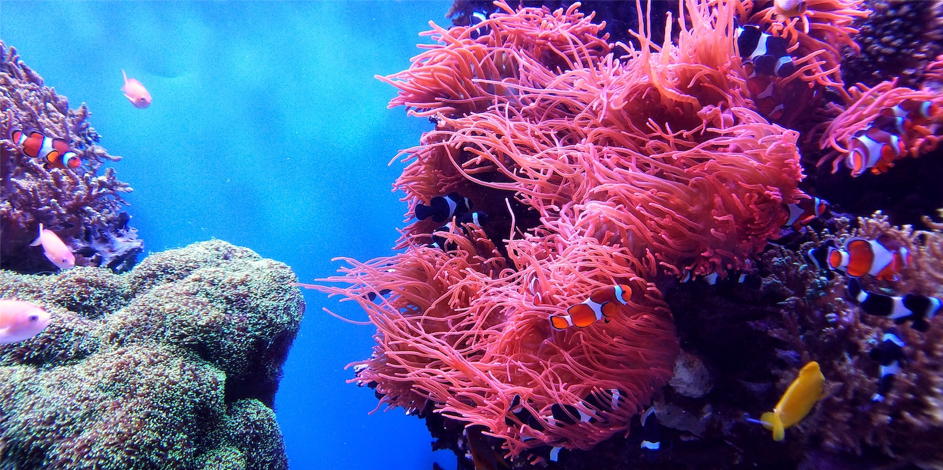

Of the five species of sea turtles in Panama’s waters, three are globally considered vulnerable to extinction, one is endangered with extinction, and another is critically endangered with extinction. Sea turtles are a vital component of the marine ecosystem as they provide support for the subsistence of the reef ecosystem and food transport throughout the world’s oceans. However, both the species and its habitat need urgent protection.

Over 60 percent of the world's 356 turtle species are threatened or extinct, making them one of the most vulnerable species on the planet. Sea turtles are threatened by human actions including harvesting turtles and their eggs, irresponsible tourism and development practices, pollution and debris, bycatch, climate change and vessel strikes. The Panama Wildlife Conservation’s Sea Turtle Project states that coastal overdevelopment, fisheries bycatch, pathogens, and climate change are all substantial threats to the survival of sea turtles.

However, lawmakers are working to change that. In 2021, Congressman Gabriel Silva introduced a law designed to preserve Panama’s sea turtles through a multi-part conservation plan that guarantees the restoration, prevention of contamination, and severe degradation of sea turtles’ habitats.

Adult female green sea turtle photographed returning to the ocean after laying eggs during the first scientific study conducted on El Playon, Isla del Rey, Pearl Islands Archipelago, Panama. Photo credit: Michael Ryan Clark

Granting Sea Turtles Rights of Nature

Following the law’s introduction, Earth Law Center (ELC) partnered with The Leatherback Project (TLP) to campaign for even more protection of sea turtles in Panama. The Leatherback Project is an organization dedicated to the conservation of the massive leatherback sea turtle throughout its global range through research, education, and advocacy initiatives aimed at mitigating fisheries bycatch, reducing plastic pollution, and combating climate change.

The two organizations have submitted a formal request that Rights of Nature be added to Panama’s law. You can read more about Rights of Nature in this ELC report.

By recognizing nonhuman species’ rights, we are taking a crucial step towards ensuring conservation is proactive rather than reactive. For example, many policies (such as the Endangered Species Act in the United States) are only enacted once a species is already endangered, at which point it can often be too late to restore the population's health. By taking an ecocentric approach rather than a human-centric approach to conservation, we are considering the sea turtle’s inherent right to exist, thrive, and evolve. This means that when humans make decisions affecting sea turtles, they need to also consider their well-being.

Olive ridley sea turtle hatchling racing towards the sea, documented for the first time on Playa Atajo, Isla del Rey, Pearl Islands Archipelago, Panama. Photo credit: Callie Veelenturf

In our society, increased legal rights means increased protection. This is seen in human rights and corporate rights, and the same would apply to animals that receive rights. Adding Rights of Nature for sea turtles would allow the conservation of the species to take a forefront in relevant decisions and would emphasize the interdependence between humans and animals. According to ELC’s Community Toolkit for Rights of Nature, adding Rights of Nature would mean:

“Recognizing Nature as an independent stakeholder in decision-making and creating a guardianship system,

Enabling representation through the standing of any person or community.”

Next Steps

Rights for non-human beings are not new! International and local recognition of non-human being’s rights to exist and flourish include:

Both San Francisco and Malibu passed resolutions protecting the rights of whales and dolphins in their coastal waters.

The ʔEsdilagh First Nation in what is now Canada (one of the six that comprises the Tsilhqot’in Nation) enacted the Sturgeon River Law (also known as the Fraser River) that states the people, animals, fish, plants, the nen (“lands”), and the tu (“waters”) have rights.

The New Zealand Government legally recognizes animals as 'sentient' beings; the Uttarakhand High Court of India ruled that “the entire animal kingdom, including avian and aquatic, are legal entities with rights; and the United Kingdom now recognizes lobsters, crabs, and octopus as sentient beings.

Ecuador has recognized the Rights of Nature on the national level.

Rivers in Colombia and New Zealand have obtained legal rights.

Panama’s proposed bill is currently in the seventh round of debates. If enacted, this would be the first time that the specific rights of a species group would be recognized in a Rights of Nature law. This bill could set a precedent for protecting the inherent rights and intrinsic value of marine species, a precedent that can encourage other nations to proactively protect sea turtles and other species.

Join ELC in our efforts to educate others and create a positive impact on the Earth!

Sign up for the ELC Newsletter

Exploring the Earth Law Toolkit with ELC

An exciting new body of law is gaining attention with legislators, activists and legal professionals around the world: Earth law. Earth law takes an ecocentric approach as opposed to a purely anthropocentric one, bringing together diverse legal movements including the legal recognition of Nature’s rights, Indigenous and biocultural rights, the rights of future generations, and the right of humans to a healthy environment, among other legal frameworks.

Earth Law Center (ELC) has been at the center of the Earth law movement from its inception, and provides expert legal advice to governments, activists, litigants and other groups or individuals navigating this relatively new legal ground. In fact, ELC literally wrote the book on Earth law, having recently released the first law school textbook presenting cases and guidance on how to use Earth Law to protect and restore Nature.

To provide an idea of how that work is done, below are some of the key tools and frameworks of Earth law that ELC has helped shape and successfully deployed.

Crafting legislation that codifies Earth law

By writing Earth-centered protections into legal codes, municipalities and regional governments can give Nature a voice within local government and create stronger protections for local ecosystems . However, with a long history of treating Nature as a resource and legislating its use only as it relates to extraction and human benefit, it is not always easy or intuitive to turn from anthropocentric to ecocentric thinking.

This is where ELC’s expertise can be deployed. Most recently, ELC worked with Save the Colorado to draft a legal model that will enable U.S. municipalities to grant rights and protections to local rivers and watersheds and establish local guardianship bodies to protect those rights. Already, several municipalities in Colorado are considering local laws or resolutions that draw from these templates (exciting news soon to follow!).

Molding the models: Creating toolkits, frameworks, guidelines and Nature’s rights declarations

In addition to working on the local or regional level to help codify protections for Nature, ELC has worked on broader reaching, cutting-edge legislation to protect Nature, including co-drafting the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Rivers and launching a standalone website where you can sign on in support, developed with ELC partner International Rivers and others. This declaration serves not only as a legal explanation for the rights of rivers, but as a legislative starting point for governments around the world interested in establishing the rights of rivers within their jurisdiction.

ELC has also played a foundational role in the Rights of Nature movement by creating toolkits and guidelines for those interested in advocating for Nature. For example, Michelle Bender, ELC’s Ocean Campaign Director, has led the creation of various Oceans-related toolkits, such as the Marine Protected Area toolkit and Rights for Coral Reefs toolkit.

ELC’s team of legal experts is writing a new DNA for legal systems around the world based on living in harmony with Nature, and making those legal models replicable and scalable.

Working with Indigenous Peoples to advance both Nature’s rights and Indigenous rights

Much as legal systems provide for guardianships for children or other individuals who cannot adequately represent or advocate for their interests, a key framework of Earth law is the establishment of legal guardianships for Nature. A useful model for this framework comes from New Zealand, which in 1978 granted legal personhood status to the Whanganui River in accordance with Maori beliefs.

While determining “who speaks for Nature” can be challenging, it is clear that it should be an independent body free of government or commercial interest and that it must represent a diversity of viewpoints. The exact guardianship model used can vary widely depending on the local community’s culture, beliefs, and traditions, but creating guardianships is a wonderful opportunity to build an inclusive governing body, and typically includes representation from local Indigenous communities, underrepresented communities, and non-profit and ecosystem protection organizations and local activists.

Advocating for the rights of future generations to a clean and healthy natural environment

In 2019, a district judge in the state of Oaxaca, Mexico, ruled in favor of protecting two of the most contaminated rivers in Mexico, the Atoyac and Salado Rivers. ELC, among others, provided an amicus brief to the court in favor of protection, and was excited to discover that the Court drew from several of the legal arguments presented in the brief, including the argument that both present and future generations have a right to a healthy environment.

Since then, the legal argument that current and future generations have a right to protected, healthy natural environments has gained ground. Most recently, Germany’s highest court ruled in April that the federal government must amend their climate law, drawing up clearer reduction targets for greenhouse gas emissions. The decision came after nine individuals, several of them young people, argued in court that as the climate law stood, it did not do enough to assure their right to a humane future.

The key frameworks outlined here are a few of the ways ELC’s legal experts are using Earth law to advance the protection and rights of Nature. ELC is excited to continue utilizing these tools and developing and advancing Earth law around the world. If you would like to get in touch with ELC’s Earth law experts, email info@earthlaw.org.

Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut’s Story: An orcas life in captivity and the efforts to free her

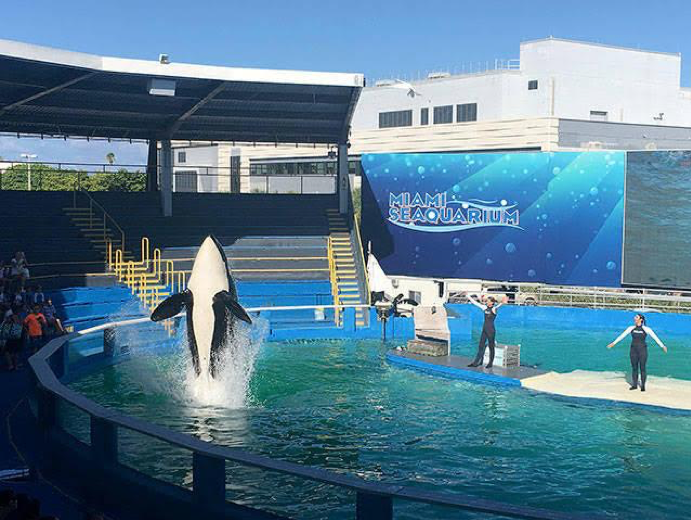

Earth Law Center recently announced our partnership with the Lummi Nation to bring Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut (first named Tokitae and later known as her stage name, Lolita) home to the Salish Sea. This is our fifth blog in this series. Our previous blogs explored the history of the campaign by the Lummi Nation, ELC’s partnership with two members of the Lummi Nation, and the culture, lives and population structure of the Southern Resident Orcas of the Salish Sea. Our most recent blog delved more deeply into the relationships of the Lummi with orcas, and the worldview of indigenous peoples, generally. This blog will delve further into the life of Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut and the decades-long legal battle to release her from the Miami Seaquarium.

By Christian Muller and Laila Remainis

Meet Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut

On August 8th, 1970 approximately 80 orcas were taken from the waters of Washington State. This event was one of the largest in history and involved dropping bombs into the water to drive the younger orcas into shallow coves. Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut was one of seven young orcas taken from her family that day. Five orcas of Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut’s pod were so seriously injured that they died shortly after. Their bodies were filled with rocks so they would sink and thus avoid public attention. For weeks after, local residents reported the cries of the remaining pod members searching the abduction area seeking their loved ones.

The abduction of Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut and other orcas profited by Ted Griffen and Don Goldsberry. The Miami Seaquarium then purchased Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut who arrived there on September 23, 1970. Her first name, Tokitae, a Salish greeting meaning “nice day, pretty colors” was changed to Lolita.

Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut’s abduction story as a mammal in captivity happened around the world and across the US. Capturing young cetaceans (whales and dolphins) from the wild to spend the rest of their lives in captivity for entertainment purposes began in the 1950s and continued until the early 1970s in the United States. This changed when the Marine Mammal Protection Act was passed prohibiting any “taking” of a mammal without a permit. Currently over 2,000 dolphins, belugas, and orcas are held in captivity internationally, with 5000 individuals having already died in captivity. Currently, there are 59 orcas in captivity in seven countries.

Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut first lived in a tank at the Miami Seaquarium with a male orca, Hugo. Taken from the coast of Washington and sold to the Miami Seaquarium in 1968, Hugo performed with Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut for ten years. Hugo’s behavior became increasingly compulsive and aggressive, which population biologists determined was caused by life restricted in a small tank. Hugo would often slam his head against the walls of the shared tank, leading to repeated injuries requiring medical and surgical attention and resulted in his death in 1980 of a brain aneurysm. Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut witnessed 12 years of this behavior as well as Hugo’s death.

Now alone, Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut lives in an 80 feet long, 35 feet wide and 20 feet deep tank (and even smaller quarters at times). Her “home” happens to also be the smallest tank for an orca in the world. Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut herself is 22 feet long. In the wild, she would have swam up to 40 miles every day and dive to depths between 100-500 feet several times a day to find food. Imagine for a moment how it would feel to be in solitary confinement: in a room where we could walk a few steps and turn around, without any windows and never being able to go outside again for the rest of our lives.

At one point, two Pacific white-sided dolphins were put into Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut’s tank, and repeatedly scarred her skin with their teeth (defensive “raking” behavior). In 2015, Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut was raked over 50 times, leaving her in need of both painkillers and antibiotics.

The shallow tank depth also leaves her vulnerable to both the hot Miami sun and major storms. In 2017 Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut was left to fend for herself in an uncovered tank during Hurricane Irma. The Seaquarium’s lockdown in response to the hurricane, left the two dolphins and Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut at risk of injury from debris, metal from a “rusty roof beyond repair,” and filtration malfunction. While free orcas are usually able to survive large storms by swimming to greater depths in the ocean, orcas in captivity are unable to.

Legal Battles to Free Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut

In the 1990s, Washington Governor Mike Lowry and Secretary of State Ralph Munro launched the first “Free Lolita!” campaign. During the next ten years, multiple organizations and foundations including the Tokitae Foundation and Orca Network formed to raise awareness about Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut’s plight. In 2003, animal rights activists, including Russ Rector issued code violations against the park for the squalid living conditions.

The movement to free Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut has spurred numerous lawsuits and petitions. These lawsuits largely cited the Endangered Species Act as well as the Animal Welfare Act. The Endangered Species Act (ESA) is the primary law in the United States for protecting imperiled species. Its goal is to develop and implement plans to recover species listed as threatened or endangered. If a species is listed, this prohibits agency actions that “may affect” a listed species, specifically prohibiting the “take” of such species, which broadly includes activities that harass, harm, or kill. The Animal Welfare Act creates and enforces that minimum standards of care and treatment be provided for certain animals bred for commercial sale, used in research, transported commercially, or exhibited to the public.

One of the first cases aiming to free orcas from captivity was filed in February 2012. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals Foundation (PETA) attorneys brought a case against SeaWorld citing the 13th Amendment. The suit claimed SeaWorld was in violation of the 13th Amendment for enslaving five orcas. PETA argued that constitutional protections against slavery are not only limited to humans. Under the 13th Amendment the orcas’ capture and forced servitude was illegal. The court dismissed the action due to lack of subject matter jurisdiction and the judge issued a statement concluding no basis to extend the 13th Amendment to non-humans. Although the case was dismissed, the news of the proceedings sparked a growth in public attention and concern for orcas used as show animals.

In 2005, the Southern Resident Orca population was listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act. The extension of the protective listing was denied to Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut. This spurred a petition in 2012 sponsored by PETA on behalf of the Animal Legal Defense Fund (ALDF), Orca Network, Howard Garrett, Shelby Proie, Karen Munro, and Patricia Sykes to include Lolita under the endangered listing of the Southern Resident population. With over 17,000 supporters, the National Marine Fisheries Service finally passed a rule in 2015 to list Lolita under the ESA.

In 2013, ALDF filed the case Lolita vs. USDA claimed that the Seaquarium’s exhibitor’s license renewal had violated the Animal Welfare Act on multiple counts. The violations included her small tank size, lack of protection from the sun and an absence of companionship (a critical issue considering the highly social nature of orcas). Seaquarium managers repeatedly rebuffed the accusations. The federal district court granted summary judgment for the USDA in 2014. The court found that while Congress established standards and procedures for the USDA to issue an exhibitor’s license, it is left to the agency to determine the standards and procedures for the license renewal process. The court determined that the USDA’s renewal process was legally permissible. The case was dismissed and lost on appeal in June 2015.

Following the death of a SeaWorld trainer, the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) implemented new restrictions between trainers and orcas to ensure the safety of both parties. While the judge ruling specified new restrictions for SeaWorld performances, the Miami Seaquarium continued placing trainers in the water with Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut. The American Legal Defense Fund (ALDF) alerted OSHA of violations. Miami Seaquarium responded with disagreement that the trainer’s lives were at any risk around Lolita. Ultimately in 2014, OSHA fined the Seaquarium $7,000 for violating the physical barrier requirement.

The year after the Miami Seaquarium was fined, Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut was officially listed under the Endangered Species Act with the Southern Resident Orca population. Several weeks after the announcement, Orca Network, PETA, and ALDF sued the Seaquarium demanding Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut be retired from entertainment and released to a seaside sanctuary. The groups proposed a retirement plan meant to transition her from to the Salish Sea. The orca advocacy team explained that the treatment and confinement of Lolita constituted a “take” (direct or indirect harassment) under the Endangered Species Act. The team cited thirteen different injuries stemming directly from the small size of her tank. The Miami Seaquarium attempted to claim that freeing her would make her more vulnerable to an injury or ailments. The initial court decision dismissed the case in 2016. It was appealed and a final decision was made in 2018. The federal judge dismissed the appeal, finding “to have taken an animal would require the action be a grave threat or have the potential to be a grave threat to the animal’s survival, and PETA did not provide evidence of conduct that met that standard.”

A recent lawsuit filed concerns Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut’s tank size and the new license granted by the USDA under the Animal Welfare Act. PETA filed the lawsuit against the USDA in 2016, and it is currently on appeal. For years, animal advocacy groups have argued that Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut’s tank is far too small for her size and intellect, and they soon had what seemed like the support of the federal agency. In a report released in 2017 by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Office of the Inspector General, an audit of Lolita’s tank found that it “may not meet all space requirements defined by the agency’s [Animal Welfare Act] regulations.” The primary measurements in question examined whether or not the trainers’ island podium infringes on Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut’s living space. However, the court found that the USDA did not violate the AWA by granting the license and the plight of Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut needed to be brought up with Congress, instead of under an administrative procedure. The case was dismissed and appealed. The status of this case is still pending.

Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut remains imprisoned. Her story illustrates the need to transform our legal system. After 50 years, it's time for Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut to go home. Her right to exist, thrive, and evolve has been denied to her from the time she was stolen from her family to today living as a for-profit entertainment item in the world’s smallest orca tank. This is why ELC is working with Squil-le-he-le (Raynell Morris) and Tah-Mahs (Ellie Kinley) of the Lummi Nation, who consider the orcas and Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut their relatives under the waves. We are exploring all legal strategies that have yet to be tried, including indigenous rights as well as the rights of Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut herself, to finally release her and see her return home.

Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut’s future and return back to the Salish Sea will be monitored by not only the Lummi Nation but also by a highly committed community of scientists and experts. International experts led by the Whale Sanctuary Project are collaborating on the development of an operational plan in anticipation of MSQ agreeing to her release. The development of the plan will draw upon the knowledge of those with specialized experience in marine mammal rescue, transport, rehabilitation, research, repatriation and long-term care. Many have been thinking about the details of Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut’s repatriation for years and believe if she is healthy, she can be transported safely. The goal is to bring her home in a responsible manner. This means ensuring everything is done in her best interest through steps such as a pre-transport evaluation, conditioning, on-site care at the Salish Sea site and long-term enrichment. Earth Law Center is committed to provide Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut her opportunity to swim once again in the Salish Sea and hope you will join us.

You can support this initiative by:

Signing and sharing the petition

Contacting Miami Seaquarium and it’s parent companies (Palace Entertainment, Parques Reunidos, EQT Group, Groupe Bruxelles Lambert, and Corporación Financiera Alba) to let them know you want to see her released!

https://aldf.org/case/challenging-the-usda-for-licensing-miami-seaquarium/

https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/environment/article16159679.html

https://www.peta.org/blog/lolitas-friends-push-forward-lawsuit-seaquariums-license/

https://www.miamiherald.com/news/business/article154928954.html

https://www.casemine.com/judgement/us/5c180e48342cca0c3163735a

http://www.orcanetwork.org/Main/index.php?categories_file=Free%20Lolita%20Update%20146

Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut and the Lummi Nation (Lhaq'temish)

Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut and the Lummi Nation (Lhaq'temish)- a story of kinship, relationship, family, connection and justice

My name is Nick Nesbitt and I am presently located in Collingwood, Ontario, the traditional land of the Petun, Anishinabewaki, Huron-Wendat, and Mississauga. Throughout my writing, I do not intend to speak on behalf of BIPOC communities but will use my voice to bring attention to matters that disproportionately affect underserved communities, lands, and people. I want to acknowledge my own privileges as a settler in what is currently Canada and emphasize my commitment to Etuaptmumk (Two-Eyed Seeing). My goal as an ally is to reduce environmental injustices by encouraging just action and demanding political accountability. I want to mention ‘The Dish with One Spoon’ treaty (created to promote peace and sharing) to highlight that we all share the same land. It is our collective responsibility to ensure this dish is never empty through respecting, honouring, and protecting the land and all life that it is home to.

Introduction

It is not completely uncommon for people to feel a deep connection with Nature. I do. And I believe I can speak for all of my colleagues at the Earth Law Center in saying, we do. After all, as humans, we are part of Nature, part of the Animal Kingdom. Unfortunately though, over the course of history, especially Western history, there has been this attempt to remove humans from Nature, to place humans above Nature, to control Nature, and to profit from Nature. And what has this led to? Ecosystem degradation on unprecedented scales, climate change, species loss, and the list goes on and on. However, one facet of this gross assault on Nature that often flies under the radar is our own intraspecies abuses. Abuses that come in the form of cultural genocide. Abuses, by which human beings have been stripped of their way of understanding and connecting to the world around them.

In June, ELC announced our partnership with two members of the Lummi Nation, Squil-le-he-le (Raynell Morris) and Tah-Mahs (Ellie Kinley); a partnership that aims to bring Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut (also known as Tokitae or her stage name, Lolita) home to the Salish Sea. 50 years ago, Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut was captured violently, and without the prior consent of her family (her mother Ocean Sun is still alive in the Salish Sea). She was placed in a small tank and has been performing shows for profit ever since. And while the release of Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut would be justice for her, it would also be for justice for Lummi Nation (Lhaq'temish), because at the heart of this matter lies a great disconnect between culture and law that must be rectified. This blog delves further into the indigenous aspect of this campaign.

"We're at a time when we all need healing," Tah-Mas added. "We're all family, qwe'lhol'mechen and Lummi people. What happens to them, happens to us."

The Lhaq'temish, “The Lummi People”

The Lummi Nation is a Native American tribe of the Coast Salish ethnolinguistic group in the Pacific Northwest region of Washington state in what is currently the United States. And to put it simply, the Lummi Nation holds a worldview that regards plants, animals, springs and trees as thinking and feeling beings that are sacred. Their human-Nature connection is one that understands and views Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut as a member of their family. What better way to learn more about them than from their own words:

Jewell James and Doug James, Jr. Lummi tribal members

We are the Lhaq'temish, “The Lummi People”. We are survivors of the great flood. With a sharpened sense of resilience and tenacity we carry on. We pursue the way of life that our past leaders hoped to preserve with the rights reserved by our treaty. We will witness and continue to carry on our Sche langen. We are fishers, hunters, gatherers, and harvesters of nature’s abundance and have been so since time immemorial. We are the original inhabitants of Washington's northernmost coast and southern British Columbia known as the Salish Sea and the third largest Tribe in Washington State serving a population of over 5,000. We are one of the signatories to the Point Elliot Treaty of 1855. We are a fishing Nation and for thousands of years we have worked, flourished and celebrated life on the shores and waters of the Salish Sea. In 1855 our ancestors signed the Point Elliot Treaty ceding lands to the United States government in exchange for our Reservation lands and guarantees to retain the rights to hunt, fish, and gather at our usual and accustomed grounds and stations and traditional territories. We have exercised these rights since time immemorial and intend to maintain these rights for our children into perpetuity. We are a Sovereign Nation and Self-Governing Nation...

We understand the challenge of respecting our traditions while making progress in a modern world. We know we must listen to the wisdom of our ancestors, to care for our lands and waterways, to educate our children, to provide family services, and to strengthen our ties with the outside community. We continue to invest in our tribal economic development and training our people to use the most modern technologies available while staying attentive to our tribal values. We envision our homeland as a place where we enjoy an abundant, safe, and healthy life in mind, body, society, environment, space, time, and spirituality where all are encouraged to succeed and none are left behind.

The commitment to ‘leave none behind’ aligns with the immediacy of this issue. As Tah-Mas explains, "Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut was taken from her family and her culture when she was just a child, like so many of our children were taken from us and placed in Indian boarding schools. Reuniting her with her family, reuniting her with us, helps make us all whole.”

A deep relationship with orcas

Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut belongs to L-pod. She belongs to the Salish Sea. She belongs to herself: she has the inherent right to be home and to be free. But, as Tah-Mahs brings to light, she also belongs to the Lummi Nation’s larger sense of family.

The Lummi term for “orca”, qwe’Ihol’mechen, translates literally to “our relations under the waves.” Like this, Lummi tradition acknowledges blackfish as kin and a cultural keystone species. Cultural keystone species are species of exceptional significance to a culture or a people and can be identified by their prevalence in language, cultural practices, traditions, diet, medicines, material items, and histories of a community. In effect, such a species influences social systems and culture and is a key feature of a community’s identity. As a cultural keystone species, the Lummi people and the qwe’Ihol’mechen have shared deep spiritual connections, kinship bonds, and cultural affinity since time immemorial. Thus, Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut belongs to the Lummi people as both a family member and as the embodiment of necessary cultural and spiritual weight and meaning.

Sadly, on August 8th, 1970, Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut was captured alongside approximately 80 other Orcas at Penn Cove, Washington. From that day on, the South Salish Sea orcas' place, as a cultural keystone species, was put into jeopardy. And the traumatic events of that day in 1970 are still being felt to this day. “They were herded in by dynamite and underwater explosions, into a cove, and they took whale after whale.” Residents of Penn Cove remember “the haunting sounds of the screams of the killer whales.” You can watch the video of Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut’s capture here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iUlbZifjoqo.

Penn Cove, place of capture

Last year Squil-le-he-le and Tah-Mahs, two Lummi members, sent a letter to the Miami Seaquarium, Palace Entertainment, and Grupo Parques Réunidos (the owners of the Seaquarium) asserting that Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut qualifies to be returned to her native home based upon the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), a federal law that requires the return of certain Native American "cultural items.” To no avail, their pleas have been ignored. Their beliefs have been disregarded. And while it seems odd that they have to do this in the first place, the disappearance of cultural items, and such disregard for Indigenous culture and worldview in western society and legal systems, unfortunately, is not uncommon.

A disconnect between culture and law

In speaking about bison and a similar biocultural atrocity, Dr. Leroy Little Bear, a respected Kainai elder, Blackfoot scholar, a professor emeritus at the University of Lethbridge in Alberta and an Officer of the Order of Canada notes that “[T]he disappearance of iconic symbols in a society means the beginning of the disappearance of a culture… Imagine what would happen to Christians if all Christian crosses and churches were gone. The disappearance of the buffalo had a similarly devastating effect on our people. Our youth now hear our buffalo songs, stories, and watch our ceremonies, but they do not see the buffalo roaming around.”

As an experiment: Reflect on your lifestyle, or way of life, the people and things that you would not be whole without. What makes you, you? Now imagine you are no longer able to perform that activity, see your loved one or that trait or object is taken from you. How do you feel?