The Lummi Nation’s Fight for ‘Rights of the Orcas’

By: Chelsea Quaies and Michelle Bender

The Earth Law Center (ELC) is leading a coalition of community groups, NGOs, scientists and indigenous peoples to gain legal rights for the Southern Resident Orcas. The Southern Resident Orcas (SROs) are an endangered species due to limits on their main food source (chinook salmon) and pollution and disturbance within the Salish Sea ecosystem. This is the third blog in the series on this campaign.

Photo by Frank Busch on Unsplash

History of the Orca of the Salish Sea

The Southern Resident Orca population of the Salish Sea once numbered over 200 individuals. In the last half-century, we have hunted them and destroyed their habitat to such a point where they now face extinction. Captures reached their peak during the 1970s, when a large portion of the population were captured and sold to different marine parks for tourist attractions.

Kurt Russo, a member of the Lummi Nation describes the events that occurred on the day in 1970, when the Orcas were captured. “They were herded in by dynamite and underwater explosions, they were herded into a cove, and then they took whale after whale.” He then discusses how the residents of Penn Cove remembered “the haunting sounds of the screams of the killer whales.” Around 80 whales were captured that day, and this is a large contributing factor to the decline in their population. Due to the significance of the captures on the Orca population, in 1976 a ban on the capture of Orcas for SeaWorld in Washington state was put into effect. After those practices were halted locally, the clan’s numbers rebounded, reaching a peak of 98 members in 1995. They now number 73 individuals.

The Orcas’ social structure is complex and stable. It is based on family groupings of pods, each containing several matrilineal lines. Because females may reach the age of 90, as many as four generations live together in pods containing 1-4 matrilines. The Orcas use similar vocal patterns, or dialects, to communicate with fellow clan members.

The Orcas form and are united by strong emotional bonds. They collaborate with one another in hunting, parenting, and teaching their young. Those most familiar with Orcas describe them as highly intelligent, curious, playful, and problem-solving beings, who experience a full range of emotions: joy, fear, sorrow, frustration, and grief. Recently, their capacity for strong emotional attachment was stunningly evident as an Orca mother carried her dead child for 17 days, over a distance of 1000 miles, before letting go.

Those who know Orcas best describe them as caring protectors of one another, not only of one another, but also, on many occasions, of humans. Throughout history, there have been accounts abound of orcas helping people who were in danger in coastal waters, and there has never been a case of a free-living Orca harming a human. Multiple examples appear in environmental scholar Carl Safina’s book, Beyond Words, What Animals Think and Feel (2015).

The movie ‘Free Willy’ of 1993, shows us not only how intelligent the Orca is, but also how deeply connected we are as sentient beings. It also foreshadows what would soon become a larger movement of freeing Orcas from captivity.

Photo by: Sacred Sea

Lummi Nation of Washington leads the way on protecting Nature

The Lummi Nation, with the traditional name Lhaq'temish, are a Native American tribe on the coast of northern Washington and southern British Columbia. They are a federally recognized tribe and self-governing nation. In 1855, the Lummi Nation signed the Treaty of Point Elliott with the United States which assured these Native American tribes would have hunting and fishing rights and reservations.

The Lummi Nation has always been a strong advocate for their rights and environmental justice. One of their largest accomplishments was their victory in the termination of the Gateway Pacific Terminal project in 2016. This terminal was due to be one of the largest coal exports port in North America, and permits for construction were released in 2011. The terminal would have increased rail-traffic across Washington State and along the Salish Shoreline, and through the Lummi Nation sacred village site of Cherry Point (Xwe’chi’eXen). Cherry Point is considered to be a sacred site due to its historical significance to their culture and their ancestors. The Lummi nation’s arguments against the terminal included that the terminal was a breach of the Treaty of Point Elliott and that by increasing exports and shipping traffic, it would increase the chance of a major oil spill in the Salish Sea and cause irrevocable environmental damage. After many years of fighting, in 2016 the Army Corps of Engineers denied the permit for the construction on behalf of the Lummi Nation’s rights.

Additionally, the Lummi have a strong connection with the Salish Sea, and have for thousands of years, with a majority of its population living on the coast and using the Salish Sea for survival including hunting, gathering and fishing. The Sea is of such great importance to this tribe they developed a campaign to protect the sea and its inhabitants. The campaign includes eliminating any new stressors to the Salish Sea, creating a healthy salmon population and producing a plan to redirect both marine vessels and development ideas. Their dedication became widely known when their journey to save Tokitae, a captured Orca from the Salish Sea that was put on display in an aquarium, became public.

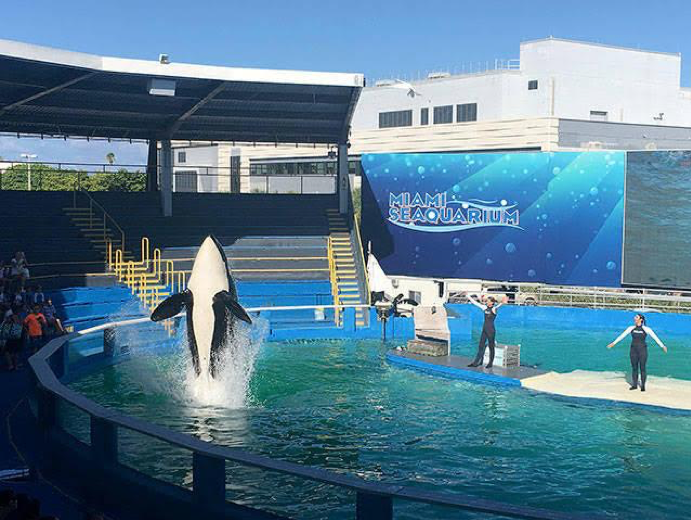

Tokitae also known by her stage name, Lolita, is a Southern Resident Orca taken from her home and family in the Salish Sea in 1970 and sold to the Miami Seaquarium. The Lummi nation relate strongly to the Xwlemi word “qw’e lh’ol me chen” which means “our relations who live under the sea” and have dedicated this word to the Orcas, their family. They relate strongly with the captured Orca, the chairman of the Lummi Nation Jay Julius has said, “Just like Tokitae, members of the Lummi Nation have endured centuries of destructive policies … policies that have separated our families, depleted our salmon runs, desecrated our sacred sites and reduced our traditional fishing area.” Members of the Lummi nation set out on a mission from Washington state to where Tokitae is located to deliver a handmade totem pole designed specifically for her.

Photo by: Sacred Sea

Tokitae is the only survivor of 45 Orcas that were captured during those years of large-scale capture. Tokitae has been living on display in the aquarium for 45 years in a small 80 ft. long, 20 ft. deep tank in hot sunny Florida, catering to the guests of the aquarium and performing two shows a day. The members of the Lummi nation have vowed to bring her back to her home in the Salish Sea, with great plans for reconnecting her with her family, “it’s long past time to return Tokiate to her native habitat and ancestral waters”, with a larger goal this will bring back peace to the Salish Sea. In recent years, the Seaquarium has been served a lawsuit over the welfare and treatment of Tokitae. In July 2019, two tribal members of the Lummi Nation (suing on their own behalf) announced an intent to sue the Seaquarium for a violation of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), in order to elicit Tokitae’s release. The 1990 federal law NAGPRA has been used for the repatriation of archaeological artifacts. Dr. Kurt Russo said. “NAGRPRA is about cultural patrimony. This is not just about a single killer whale and two people, it’s about an essential sense of belonging that cannot be adequately expressed in legal language.”

The goal of her relocation from the Seaquarium back to the wild involves rehabilitation efforts including medical care and supreme husbandry care inside her seapen which will be in a protected area, where her family can come visit. She will then be gradually re-trained for her release into the wild after completion in rehab. The director of the non-profit group Orca Network, Howard Garrett said in an interview, “We would like to see her enjoy her life. We would like to see her be able to swim free in the waters where she grew up.”

The world is also starting to see the harm in keeping cetaceans in captivity. Animal Welfare Institute, PETA and many other organizations and people are fighting to end this practice. You may have seen the movie Blackfish, highlighting this issue, or the use of the hashtag #EmptytheTanks. As a result of coordinated activism, entire countries have banned the practice altogether. Earlier in 2019, Canada passed legislation banning the captivity of whales and dolphins (those already held can remain). Chile, Australia and Costa Rica, amongst others, have also stopped the capture of wild marine mammals with major fines in place if someone is caught doing so.

Within the United States there has also been major changes in the captivity of cetaceans, resulting in legislation banning display of whales and dolphins in New York, South Carolina, Hawaii and California.

Some countries and states have taken the ‘Empty the Tanks’ Campaign one step further, recognizing marine mammals as sentient beings that have rights. On May 20, 2013, India’s Ministry of Environment and Forests banned the keeping of captive dolphins for public entertainment. A statement from B.S. Bonal of the Central Zoo Authority declared that “confinement in captivity can seriously compromise the welfare and survival of all types of cetaceans by altering their behavior and causing extreme distress.” The Ministry even declared that dolphins “should be seen as ‘non-human persons’ and as such should have their own specific rights.” In a policy statement, the ministry advised state governments to reject any proposal to establish a dolphinarium “by any person / persons, organizations, government agencies, private or public enterprises that involves import, capture of cetacean species to establish for commercial entertainment, private or public exhibition and interaction purposes whatsoever.”

Additionally, in California, both San Francisco and Malibu passed resolutions in 2014, expanding towards the notion that cetaceans have rights, namely the right to move freely in their habitat. The Marine Life Proclamation passed in Malibu in 2014 resolved that whales and dolphins have the right to free and safe passage and “encourages citizens of the world to do all within their power to protect them and preserve the oceans in which they were destined to spend their lives.” San Francisco likewise passed the “Free and Safe Passage of Whales and Dolphins in San Francisco’s Coastal Waters” resolution supporting the free and safe passage of cetaceans in their waters and to be free from captivity. Finally, in 2010, a conference held on Cetacean Rights in Helsinki produced a Declaration on the Rights of Cetaceans with the goal of universal adoption.

Campaign for the Rights of the Southern Resident Orcas

The people of Washington State are worried for the Southern Resident Orcas and the lack of governmental and political response in trying to support the recovery of these animals, including their habitat and food supply. The Lummi nation as well as many others, including the Earth Law Center (ELC), believe that systemic change is needed in order to save the population from extinction.

Late 2018, ELC joined with Legal Rights for the Salish Sea (a community group based in Gig Harbor, WA) to create a coalition of groups working towards recognizing the rights of the Southern Resident Orcas. Together, the coalition has made significant strives towards realization of its goals. In the last year alone, the campaign has been featured in over 10 articles. Partners in Pender Island, BC, Canada, have a petition sitting with the Pender Island Trust Council, and the group is working with other local and state policymakers to pass resolutions in support.

The Campaign is in line with the Lummi Nation’s beliefs and goals. Recognizing the rights of the Southern Resident Orcas gives them a higher form of protection, both legally and judicially. These rights include, but are not limited to, the right to life, autonomy, culture, adequate food supply and free and safe passage. Specifically, if rights to free and safe passage are codified for the Orcas, this could create implications and a legal framework in support of the Lummi Nation’s fight to free Tokitae back to the Salish Sea. Therefore, supporting the beliefs and the rights of the indigenous peoples surrounding the Salish Sea is a top priority within the Colation’s campaign.

“Our belief is that not only the salmon and qwe ‘lhol mechen [Orca], but all the air, the land, the water, the creatures, they all have inherent rights,” Kurt Russo, Lummi Nation.

To learn more about the lawsuit, or the Lummi Nation’s Salish Sea campaign visit here.

You can learn more about the ‘Rights of the Orcas’ here and by emailing mbender@earthlaw.org.

You can also support our efforts by donating today.