Earth Law Center Blog

Philippines Establishes Guardians for Marine Mammals

Rights of Nature has taken root in the Philippines. ELC and Philippines Earth Justice Center are exploring how to advance the movement and incorporate the Earth Law Framework for Marine Protected Areas.

View of the Philippines Sea from Cape Maubito, Taiwan. Photo by CEphoto, Uwe Aranas

By Michelle Bender and Darlene Lee

Rights of Nature has taken root in the Philippines. Earth Law Center and Philippines Earth Justice Center are exploring how to advance the movement further, specifically how to incorporate the Earth Law Framework for Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) into the country’s National System of MPAs.

The Philippines Sea: Unparalleled biodiversity

Located in the Pacific Ocean, 7,100 islands and 36,000 kilometers of coastline make up the country of the Philippines.[i]

Over 2,000 fish species, 22 species of whales and dolphins, 900 species of seaweed and more than 400 species of coral call the Philippine Sea home.[ii] The ocean matters to people too, with over 1 million Filipinos depending on it for their livelihoods (equal to 4 percent of the country’s gross national product).[iii]

Not many people know that the Philippines hosts unique and unparalleled marine biodiversity. Part of the Coral Triangle, the Philippine Sea is often referred to as the “Amazon of the Seas” where 70% of all known coral species in the world are found.[iv] Hence, protecting the biodiversity of the Philippine sea is important not just to the neighboring countries but to the larger marine ecosystem.

Bottom of the Philippine Sea By Carljohnthegreat [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

Threats to the Philippine Sea

Pollution, fishing practices like dynamite fishing, and climate change threaten the health of the Philippine sea. Oil spills have continually impacted the Philippine sea and local communities. For example, in 2008 a coal spill off the coast of Bolinao caused an estimated 55 million dollars in damage.

As a result, three quarter of the mangroves have disappeared and 54% of the coral reefs are “badly damaged.”[v]

Endangered species in the Philippine sea include: hawksbill sea turtles, giant clams, net coral, false flower coral, sei whales, blue whales, fin whales, loggerhead turtles, humphead wrasse, green turtles, spiny turtles, and frog-faced soft shell turtles among many others.[vi]

Focus on Philippine Rise

Philippine Rise (formerly known as Benham Rise) is a 13 million hectare undersea volcanic ridge region to the east of the Philippines.[vii] An ecologically important and biodiverse marine area, the Rise provides the only spawning ground for Pacific Bluefin Tuna, and the only place in the Philippines with 100% coral cover.[viii] It is considered “one of the Philippines’ last, best chances to protect old-growth coral reefs.”[ix]

The bluefin tuna, endangered for several years, has suffered a catastrophic decline in stocks in the Northern Pacific Ocean, of more than 96%. At current rates, the species will soon be functionally extinct in the Pacific. More than nine out of 10 of the species recently caught were too young to have reproduced, meaning they may have been the last generation of the bluefin tuna.[x]

The Philippines government has taken great strides to protect this area. On May 15, 2018, President Rodrigo Duterte signed a proclamation declaring 50,000 hectares of the Rise as a marine reserve. Approximately one third of this area was also designated as a no-take zone, closed to all human activities besides scientific research. Additionally, 300,000 hectares are managed with a ban against “active fishing gears.”[xi]

Considered a “potentially rich source of natural gas and other resources such as heavy metals,”[xii] the Philippines Rise faces threats from foreign oil extractors. Local groups have organized to protect this area.

Benham Rise Map By National Mapping and Resource Information Authority (NAMRIA) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Lawsuit for Tanon Strait

Gloria Ramos, (now executive director of Oceana Philippines) and Rose-Liza Eisma-Osorio, created the Philippine Earth Justice Center.

The Philippine Earth Justice Center (PEJC) is a non-stock and non-profit corporation which was established to provide legal assistance to victims of environmental injustice, conduct policy research on the environment, advocate policy reforms, assist in building local capacities for environmental protection and promote sustainability and protection of human rights.

PEJC usually joins private individuals, helping them to assert their rights as a steward in various cases. It is also a duly recognized organization in the pursuit of the right to a balanced and healthful ecology in accord with the rhythm and harmony of nature guaranteed under the 1987 Philippine Constitution. PEJC is assisting victims of coal ash disposal in a community near a coal-fired power plant in Naga, Cebu. Other cases have involved indigenous peoples fighting against small-scale mining activities within their ancestral domain in Southern Philippines, coastal communities preventing reclamation activities, and fisherfolks with their communities asserting preferential rights over their municipal waters.

Philippine law permits any citizen to file an action before the courts for violations of environmental law. The Philippines are leaders of crafting environmental laws in the world. “Imagine, in the U.S., you can only go to court if you were already harmed by exploitative activities. In the Philippines, you can sue before you get harmed. It is preventive,” Gloria Ramos, Oceana said.

The Philippines Earth Justice Center sued the government to protect the Tañon Strait from oil exploration and development. The Strait is the largest marine protected area in the Philippine sea.

Titled “Resident Marine Mammals of the Protected Seascape Tañon Strait et. al. V. Secretary Angelo Reyes et al." the marine mammals gained standing in the case. The Philippines Earth Justice Center was dubbed by the media as “guardians of marine mammals” in the case (and the name has followed them since). They contended “that there should be no questions of their right to represent the resident marine mammals since the primary steward, the government, had failed in its duty to protect the environment pursuant to the public trust doctrine.”

The court noted “the right to a balanced and healthful ecology, a right that does not even need to be stated in our Constitution as it is assumed to exist from the inception of humankind, carries with it the correlative duty to refrain from impairing the environment.” Also, due to the Constitution’s mandate to “protect and advance the right of the people to a balanced and healthful ecology in accord with the rhythm and harmony of nature” the court ruled in favor of nature, and reversed the contract that was granted to the company Japex allowing oil exploration activities, determining “no energy resource exploitation and utilization may be done in the protected seascape.”

This important precedent can help protect Benham Rise, ensuring the government adheres to legal frameworks such as the National Integrated Protected Areas System Act of 1992, and that community members adhere to their duties as stewards for the environment.

What’s next for the Philippines Sea?

The country already allows the rights for citizens to sue on behalf of the environment. The next step is to recognize the rights afforded to nature in law.

Communities are pushing for introduction of this legal framework in the country. On World Environment Day (June 5th), a wide caravan of groups called upon “increased protection for the environment and upholding of the rights of nature.”[xiii] Named “Salakyag” the march pushed for “a return to the culture of interconnection and full embrace of nature.”[xiv]

Gloria notes that “What is good for the environment is good for business, so we really need to change the mindset that protecting the environment and business interests are mutually exclusive.” This is what the rights of nature framework provides. It requires us to balance the rights of nature with humans, and ensures that economic benefits are not privileged over the benefits of a healthy environment.

Next steps to secure rights for the Philippines Sea

Rose-Liza Eisma-Osorio is working to “increase advocacy and work with groups calling for the rights of nature in the Philippine legal system.” This includes including rights of nature in future court cases to protect the environment and incorporating the Earth Law Framework into the national system of MPAs.

The current framework is the National Integrated Protected Areas Act (NIPAS) of 1992, recently amended in 2018. This Act creates the system for protected areas in the Philippines and provides for their management. Under the Act, all recognized protected areas must have a management plan within one year, and a management board created for each. These boards must be comprised of government, local community, NGO, indigenous, private sector and academic institution representatives. Per the precedent set in the Tanon Strait case, there exists an opportunity for a representative to assume the role of the Guardian for the protected area. The introduction of guardians who represent the protected area’s interest is one way to incorporate the Earth Law Framework into NIPAS.

Additionally, environmental groups in the Philippines are currently drafting a rights of nature law to present at the National level. This initiative is also being supported by the Catholic Church.

How you can help

Stay informed by signing up for ELC’s monthly newsletter

Volunteer for this initiative

Donate to the cause

Read more about the Philippine Earth Justice Center, Inc.

[i] https://www.greenpeace.org/seasia/ph/PageFiles/533258/OD-2013-PH-SEAS.pdf

[ii] Id.

[iii] Id.

[iv] http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files

[v] https://oceana.org/blog/saving-philippines-last-untouched-coral-reefs

[vi] https://owlcation.com/stem/The-Top-Ten-Critically-Endangered-Animals-in-the-Philippines

[viii] https://amp.rappler.com/nation/202776-dolphins-shaped-environmental-laws-philippines-benham-rise?__twitter_impression=true

[ix] https://oceana.org/blog/saving-philippines-last-untouched-coral-reefs

[x] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2013/jan/09/overfishing-pacific-bluefin-tuna

[xi] https://amp.rappler.com/nation/202776-dolphins-shaped-environmental-laws-philippines-benham-rise?__twitter_impression=true

[xii] https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/iq/164514-fast-facts-benham-rise

[xiii] http://www.kagay-an.com/salakyagstop-killing-environmentuphold-rights-nature/

[xiv] http://www.kagay-an.com/salakyagstop-killing-environmentuphold-rights-nature/

Seeds of Hope for Earth Law in the Philippines

Earth Law Center and Philippines Earth Justice Center partner to advance the Rights of Nature movement, and integrate Earth Law concepts into their existing conservation efforts.

By WolfmanSF [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

By Margarita N. Lavides and Darlene May Lee

While the Philippines needs to strengthen its law enforcement capacity, it will also benefit from building on its rich well-crafted environmental policies with a new model of environmental governance focused on well-being and guided by principles of sustainability, ecosystem health, precaution, interconnectedness and inclusiveness. Read on to find out more about how Earth Law Center and Philippines Earth Justice Center partner to advance the Rights of Nature movement, specifically how to incorporate the Earth Law Framework for Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) into the country’s National System of MPAs.

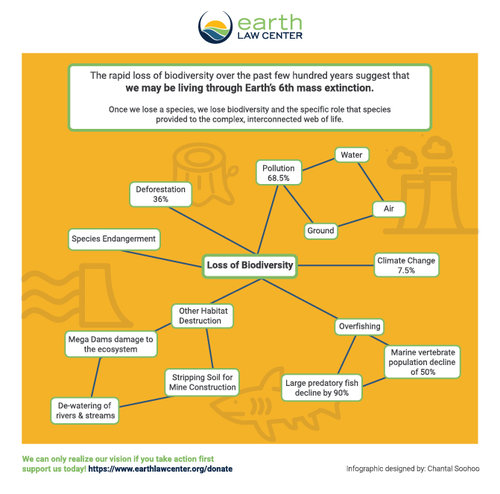

The Philippines is one of 18 mega-biodiverse countries of the world, containing two-thirds of the earth’s biodiversity and between 70% and 80% of the world’s plant and animal species. The Philippines ranks fifth in the number of plant species and maintains 5% of the world’s flora. Species endemism is very high, covering at least 25 genera of plants and 49% of terrestrial wildlife, while the country ranks fourth in bird endemism and considered to host the most number of marine species in the world. The Philippines is also one of the world’s biodiversity hotspots with at least 700 threatened species, thus making it one of the top global conservation areas.[1][2]

Philippines ranks 7 globally for coastal governance laws

Infographic of Biodiversity in the Philippines (Source: Philippine Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, PBSAP 2015-2028)

The Coastal Governance Index [3] ranks the Philippines 7th out of twenty maritime countries across the globe for its good track record of well-crafted environmental laws. While some current proponents of constitutional change include proposed environmental rights in its bill of rights, the current Philippine Constitution promotes a right to a healthy environment.

The 1987 Philippine Constitution [4] provides that the State shall protect the nation’s marine wealth in its archipelagic waters, territorial sea, and exclusive economic zone, and reserve its use and enjoyment exclusively to Filipino citizens. The same Constitution provides that the State shall protect and advance the right of the people to a balanced and healthful ecology in accord with the rhythm and harmony of nature. It also provides for the protection of the preferential rights of subsistence fishers and local communities in the use of inland and offshore fishing resources and provides for support in the conduct of their livelihoods.

With regard to integrated coastal management, 75 related major laws/policies have been enacted and national programs implemented (from 1800s to 2018). These include the landmark legislations on local government code; a fisheries code; an act on national protected areas system; a national biodiversity strategy and action plan and a proclamation on the establishment of Benham Rise Marine Reserve. These laws and policies, among other outcomes, allowed for local government and communities to better manage their natural resources, especially in coastal areas; increased the areas for critical habitat and protected areas; provided the roadmap for biodiversity protection and management and established the largest and biodiversity-rich marine protected area.[5] Beyond the work of Filipino legislators, these environmental laws materialized due to many outstanding environmental law practitioners and an active civil society organizations.

Activists protecting the natural environment in the Philippines

By Shubert Ciencia (Flickr: Manila Bay) [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

In 1993, Atty. Antonio Oposa Jr. represented 43 Filipino children who initiated an action against the Philippine Government for the misappropriation of the country’s forest resources. Despite being dismissed at trial court, Oposa took it to the Supreme Court who upheld the legal standing and the right of the children to initiate the action on behalf of generations yet unborn - establishing the “Oposa Doctrine” as it is known now in Philippines and global jurisprudence. Oposa also waged a ten-year legal battle against eleven government agencies to clean up Manila Bay, ultimately winning a decision from the Supreme Court who ordered the offending agencies to clean up Manila Bay.[6]

Attys. Gloria Ramos and Rose Liza Eisma-Osorio defended the rights of marine mammals to a healthful ecology in Tanon Strait preventing a mining company from oil exploration in the Strait in a precedent setting Supreme Court decision in 2015.[7] They are currently exploring a specific Earth Law initiative with Earth Law Center which seeks to incorporate the principles of the Framework for Ocean Rights.

Many lower court cases can bring additional optimism in this era of pessimism. Residents of Bantayan Island, Cebu sued and won to protect their coastal areas from tourism business that violates environmental laws. Atty. Gloria Ramos gained (and later extended) a Temporary Environmental Protection Order (TEPO) to stop a local coal power plant from transporting toxic coal combustion residuals outside premises. Concerned Citizens of Iligan City and the Center for Alternative Legal Forum and Injustice Inc jointly filed for and won a TEPO to prevent illegal logging. While environmental lawyers and activists continue to fight against environmental violations, other members of civil society organizations also seek to implement innovative solutions towards a more just and sustainable environment and society.[8]

Pioneering environmental NGO, Haribon Foundation, founded in 1972, has sparked the environmental movement through its research and advocacy work for Critically-Endangered Philippine Eagle which through the years expanded the work into national protected areas system, threatened species and community-based and local government led conservation and resource management. In 1999, it organized a national network of fisher-MPA managers called Pamana Ka Sa Pilipinas from 122-MPA-member sites across the country which became an important national player in advancing the cause of small scale fisheries and marine conservation.[9]

International NGOs like Oceana-Philippines while working for fisheries reform, was one of the leading catalysts in the presidential proclamation of Philippine Rise (Benham Rise) into a largest marine reserve in the country.[10] A growing number of universities now engage with government and NGOs towards building a more sustainable environment and development. University of the Philippines and other leading universities are active not only in its knowledge generation but leveraging impact by influencing environmental policy and advocacy. The church is also active in its campaign for a more just and sustainable communities. It is quite common for Catholic priests and lay persons to lead environmental campaigns and advocacy against coal mining and other environmental violations across the country.

Current protections remain insufficient for ecosystem and species health

Yet despite all this activity, the country’s natural ecosystems and species continue to suffer. In a country level study, 59 fish names were identified to be at risk of local extinction, with large and slow-growing reef fishes such as Giant Grouper, Bumphead Parrotfish, Humphead Wrasse, declining as much as 88% in catch since the 1950s due to overfishing and vicious cycle of poverty.[11] This is aggravated by impacts of climate change and habitat degradation.

In a national survey of coral reefs, it was reported that there is a marked decline in hard coral cover across the country since the 1970s, with loss of reefs in excellent condition and more than 90% of the reefs in poor condition.[12] No wonder a typical old Filipino fisher, during our interviews with them across the country would say: The present fishers’ catch for one month is nothing compared to our fish catch for just one week.

Land ecosystems suffer equally. Dr. Mundita Lim, former Director of Philippine Biodiversity Management Bureau and currently Executive Director of ASEAN Center for Biodiversity laments, “In the Philippines, we have lost almost 93 percent of our original forest cover since the 1900’s. In 2008, 58 out of the 206 then known mammal species native to the Philippines were included in the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red Data List of Threatened Species.[13] This is a number that is significantly large, considering that more than half of our native mammalian species are found only in the country and nowhere else in the world.”[14]

Coupled with the alarming rate of biodiversity loss is the continued discoveries of new species which all the more fortify the position for a more strengthened environmental governance and enforcement. From 2005 to 2012, there were 151 new species of birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians and plants discovered. In Luzon alone, there were 300 new species discovered in 2011 by California Academy of Sciences.[14]

While the national government of the Philippines has been addressing climate change and environmental challenges, inconsistencies abound such as the continued government’s permission to mine coal despite local governments’ and communities’ opposition in many cases. Continued logging in natural forests and rampant overexploitation of wildlife continue to threaten native ecosystems and species while enforcement of environmental protection laws remains weak. So despite the successful establishment of a host of environmental protection laws, the ecosystems and species of the Philippines remains imperiled.

Rights of Nature (RoN) and Integrated Coastal Management(ICM): A Symbiosis

Earth Law or earth jurisprudence, including Rights of Nature, could help strengthen and evolve the current legal protections of nature in the Philippines. Earth Law is an ethical framework that recognizes nature’s right to exist, thrive and evolve - enabling nature to defend these rights in court, just like corporations can. Earth Law has theoretical origins in 1970s but since 2006 when the first Rights of Nature legislation was implemented in the US has been gaining strength through constitutional provisions or national law (Ecuador, Bolivia) and local ordinances (New Zealand, India, Mexico and in three dozen US cities and municipalities).

Since 2003, a series of government laws and policies establishing ICM as a national strategy to ensure sustainable development of the country’s coastal and marine environment and resources and including guidelines for its implementation, has been issued. In 2016, a Senate Bill to strengthen the adoption of ICM as a national coastal resource management strategy has been filed.[5]

ICM-related policy issuances emphasized that ICM covers all coastal and marine areas, addressing the inter-linkages among associated watersheds, estuaries and wetlands and coastal seas by all relevant national and local agencies5. This means that the management approach should encompass forest, river and marine areas due to their interconnectedness. This can easily be seen in impacts of land- and sea-based human activities such as agriculture, deforestation and overfishing.[15, 16, 17] Because of ICM’s integrative characteristic consistent with the principles of RoN, ICM is used here to show common principles applied to both RoN and ICM.

According to government-issuances on ICM, among the identified elements of ICM programmes across socio-ecological systems, are the establishment and management of marine protected areas and its networks. Thus MPA and MPA network programmes sit well within ICM programmes and both have principles consistent with RoN.

While many will argue that legislating for RoN may not yet be timely for the Philippines due to its current political climate, poverty-related social and environmental problems and the country’s low score in enforcing the law [2]; but it cannot be denied that the country is also laden with seeds of hope that can germinate into an Earth Law regime and bearing fruits from its future Rights of Nature legislations and implementation.

While we embark on this process with realistic optimism, environmental lawyers and activists and other civil society organizations are enjoined to continue to optimize the use of existing environmental rights constitutional provisions and other related environmental laws and policies towards a just and sustainable Philippines.

How Can You Help Crystallize an Earth Law Regime in the Philippines?

Stay informed by signing up for ELC’s monthly newsletter

Donate to the cause

Volunteer for Earth Law initiative of ELC and Philippine Earth Justice Center, Inc

1. https://www.cbd.int/countries/profile/default.shtml?country=ph

2. Carpenter and Springer (2005) The center of the center of marine shorefish biodiversity: the Philippine Islands. EnviBio Fish, 72: 467-480.

3. EIUL Economist Intelligence Unit Ltd. (2015) Coastal Governance Index

4. Philippine Constitution (1987)

5. Forest Foundation (2018) ICM and ICM Policies in the Philippines Prepared by Dr. MNLavides

6. https://www.films.com/ecTitleDetail.aspx?TitleID=76342

7. Bender & Lee (2018) Philippines Establishes Guardians of Marine Mammals Earth Law Center www.earthlaw.com

8. Lagura-Yap et al. (Undated) Environmental Justice in Philippine Courts

9. http://www.haribon.org.ph/index.php/haribon-foundation/history

10. https://ph.oceana.org/

11. Lavides MN et al. (2016) Patterns of coral reef finfish species disappearances inferred from fishers’ knowledge in global epicentre of marine shorefish diversity. PLoS One, 11(5): e0155752. Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155752

12. Licuanan AM et al. (2017) Initial findings of the national assessments of Philippine coral reefs. Philippine Journal of Science, 146(2): 177-185.

13. IUCN (2008) Red Data List of Threatened Species

14. Philippine Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (PBSAP) 2015-2028

15. Makino A et al. (2013) Integrated planning for land-sea ecosystem connectivity to protect coral reefs. Biological Conservation, 165: 35-42

16. Reed et al. (2017) Have integrated landscape approaches reconciled societal &environmental issues in the tropics? Land Use Policy 63: 481-492.

17. Oleson KLL et al. (2017) Upstream solutions to coral reef conservation: The pay-off of smart and cooperative decision making. Journal of Environmental Management, 191: 8-18.

Rights for the Southern Resident Killer Whales

ELC & partners are seeking rights recognition for the endangered Southern Resident Killer Whale population and the Salish Sea. Learn more about orcas and the threats to their survival.

Source: NOAA (http://www.afsc.noaa.gov/Quarterly/amj2005/divrptsNMML3.html)

By Michelle Bender and Darlene Lee

Earth Law Center is partnering with Legal Rights for the Salish Sea (Gig Harbor community group), the Nonhuman Rights Project and PETA to seek rights recognition for the endangered Southern Resident Killer Whale population and the Salish Sea.

A Brief Primer on Orcas

Most of us easily recognize the distinctive black and white coloring of Orca Whales. But did you know that they are the largest member of the 35 species in the oceanic dolphin family, which first appeared about 11 million years ago?[i] Considering Homo Sapiens have been on Earth just 200,000 years[ii], perhaps our perspective on these highly intelligent and social fellow Earthlings needs to evolve.

"Whales represent the most spectacularly successful invasion of oceans by a mammalian lineage," said Michael Alfaro, UCLA assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology. "They are often at the top of the food chain and are major players in whatever ecosystem they are in. They are the biggest animals that have ever lived. Cetaceans (which include whales, as well as dolphins and porpoises) are the mammals that can go to the deepest depths in the oceans.[iii]

Unlike other whales who have shrunk in size over time, Orcas have become larger over the last 10 million years. Also unlike other whales, they eat mammals, including other whales. "If we look at rates of body-size evolution throughout the whale family tree, the rate of body-size evolution in the killer whale is the fastest," Graham Slater, a National Science Foundation–funded UCLA postdoctoral scholar in Alfaro's laboratory said.[iv]

Contrary to their reputation in popular culture and the much-publicized attacks by captive Orcas, no recorded case of a free-ranging orca ever harming a human exists. Even when orca mothers are violently pushed away with sharp poles so their young can be wrestled into nets and loaded onto trucks, they have never attacked a human being.[v]

Types of Orca Clans

The IUCN reported in 2008, "The taxonomy of this genus is clearly in need of review, and it is likely that O. orca will be split into a number of different species or at least subspecies over the next few years." The three types include[vi]:

Resident: Feeding on fish and squid, these Orcas live in complex and cohesive family groups called pods. They visit the same areas consistently. British Columbia and Washington resident populations are amongst the most intensively studied marine mammals anywhere in the world. Transients and residents live in the same areas, but avoid each other.

Source: NOAA

Transient: The diets of these whales consist almost exclusively of marine mammals. Transients generally travel in small groups, usually of two to six animals, and have less persistent family bonds than residents. Transients vocalize in less variable and less complex dialects. Transients roam widely along the coast. Transients are also referred to as Bigg's killer whale in honor of cetologist Michael Bigg.

Offshore: These orcas travel far from shore and feed primarily on schooling fish and may also eat mammals and sharks. Offshores typically congregate in groups of 20–75, with occasional sightings of larger groups of up to 200. Little is known about their habits, but they are genetically distinct from residents and transients. Offshores appear to be smaller than the others.[vii]

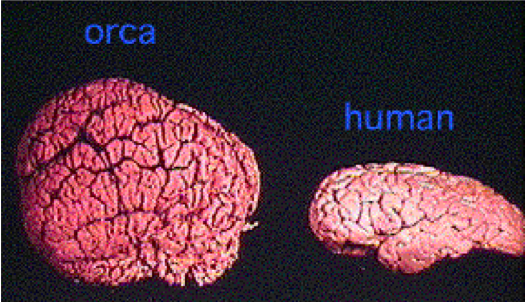

Orcas have a brain part that humans don’t

Not only do they have their well-documented senses of humor and empathy and mischievousness, Orcas possess a paralimbic cleft which "may enable some brain function we can't even envision because we lack it," David Neiwert writes in Of Orcas and Men, his breathtaking survey of orca science, folklore, and mystery. "Scientists who examine their brains are often astonished at just how heavily folded these brains are."

The more wrinkles and folds a brain has, the more data it can handle and the faster it can process information. This dense folding is called gyrification, and orcas have "the most gyrified brain on the planet." Their gyrencephaly index is 5.7 compared to human beings' 2.2.

Scientists have also found highly developed parts of the orca brain they believe are associated with emotional learning, long-term memory, self- awareness, and focus.[viii]

More about the Southern Resident Orcas

As of June 2018, only 75 Southern Resident Orcas remain: J pod has 23 members; K pod has 18; and L pod has 34.[ix]

Dr. Michael Bigg, who pioneered field research on orcas in the early 1970's first coined the name. The three Southern resident pods, known as J, K and L pods, usually travel, forage and socialize throughout the inland waters of the Salish Sea (Puget Sound, the San Juan Islands, and Georgia Strait) from late spring through late summer seeking chinook salmon, which provide about 80% of their diet. [x]

An extended family forms the Southern Resident community. Both male and female offspring remain near their mothers throughout their lives. The average size of a matriline is 5.5 animals. Because females can reach age 90, as many as four generations travel together. [xi] No other mammal known to science maintains lifetime contact between mothers and offspring of both genders. Unlike all other mammals except humans, orca females may survive up to five decades beyond their reproductive years.[xii]

These matrilineal groups are highly stable. Individuals separate for only a few hours at a time, to mate or forage. Each individual has a unique fin shape, markings and color patterns. When Southern resident pods join together after a separation of a few days or a few months, they often engage in "greeting" behavior. With one exception, a killer whale named Luna, no permanent separation of an individual from a resident matriline has been recorded. [xiii]

Securing Orca Rights

When an individual is removed from his or her home by force, imprisoned, made to work, and forever denied their freedom, it’s called “slavery.” In October 2011, PETA filed a lawsuit against SeaWorld on behalf of five wild-captured orcas seeking a declaration that these five orcas are slaves and subjected to involuntary servitude in violation of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Joined by three orca experts and two former SeaWorld trainers, PETA’s lawsuit asserts that the conditions under which these orcas live constitute the very definition of slavery.[xiv]

PETA’s briefs cited more than 200 years of U.S. Supreme Court precedent, including such landmark cases as Dred Scott, Brown v. Board of Education, and Loving v. Virginia, to establish that the orcas’ species does not deny them the right to be free under the 13th Amendment and that long-established prejudice does not determine constitutional rights. Harvard law professor and constitutional scholar Laurence H. Tribe said: “People may well look back on this lawsuit and see in it a perceptive glimpse into a future of greater compassion for species other than our own.”[xv] (read the full review article here: http://www.mediapeta.com/peta/PDF/FW-13th-Amendment-Law-Review.pdf).

Blackfish the film captures public attention

In January 2013, the documentary Blackfish premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, telling the story about Tilikum, a performing killer whale that killed several people while in captivity.[xvi] A little more than three years later (a period marked by sustained activism, multi-platform distribution, and media coverage) SeaWorld officially announced on March 17, 2016 that it will officially end its orca breeding program and end orca shows at all of its theme parks.

By 2015, the stock price of SeaWorld had declined by 84 percent.[xvii] A California state lawmaker proposed legislation in April 2014 that called to ban California aquatic parks from featuring orcas in performances; although the proposed law was unsuccessful, it garnered national media coverage.[xviii]

In January 2017, Seaworld San Diego held its last Orca show, prompted by years of outcry and falling attendance.[xix] Parks in Orlando and San Antonio will end their shows by 2019.

Southern Resident Orca Rights Initiative

Securing rights for the endangered Southern Resident Killer Whale population can help stave off extinction for these highly intelligent and social animals who are critical to the health of the Salish Sea marine ecosystem. Michelle Bender, Ocean Rights Manager, notes,

“To truly protect Southern Resident killer whales, now and in the long term, we urgently need to recognize and codify their rights. Scientific studies and human experience of these animals have made clear that they are self-aware and autonomous, with complex emotional and social lives—and we humans are the cause of their endangerment. As autonomous beings, Southern Resident killer whales cannot survive, much less thrive, without legislation that protects their habitat as a matter of right and ensures that human activities do not infringe on their bodily liberty and integrity and prevent them from living life as they were meant to: freely in the open ocean, with an ample supply of their natural food source and without pollutants in their bodies. A rights ordinance is, without a doubt, the best way to do this,” notes Courtney Fern, the Nonhuman Rights Project’s Director of Government Relations.

Lawyer Elizabeth M. Dunne, Esq. who focuses on advancing and defending the rights of local communities and ecosystems in partnership with the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund is part of the larger consortium ELC is building to secure rights for the Salish Sea. She notes:

"Our current anthropocentric (human centered) legal system is out of line with our ecological reality. Recognizing that nature has rights harmonizes our legal system with what we know to be true -- humans cannot dominate, and quite literally issue “permits” to destroy (as provided by environmental regulations), our natural and animal communities without severe consequences. With the understanding that non-human inhabitants of the Earth, such as the southern resident orcas, are sentient beings comes the recognition that they, too, have rights. Not as “persons”, but in their own right as living beings with whom we co-exist. Recognizing that the southern resident orcas have enforceable rights in their own right is critical to their continued existence. With only 75 left, it is self-evident that legislation, such as the Endangered Species Act, has largely failed them. Indeed, our entire legal structure has failed them, and us, by perpetuating the delusion that it is only humans (and corporations) who have rights. I hope that we all intuitively know that by killing life on this planet, we are killing ourselves, and that we cannot thrive in a legal structure that fails to pay heed to our interconnectedness. In dire circumstances lies hope for a paradigm shift."

Act today to save the Southern Resident Killer Whales!

More about the Southern Resident killer whale Coalition Partners

The Nonhuman Rights Project (NHRP) is the only civil rights organization in the United States working through litigation, public policy advocacy, and education to secure legally recognized fundamental rights for nonhuman animals. https://www.nonhumanrights.org/

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) is the largest animal rights organization in the world, with more than 6.5 million members and supporters. PETA focuses its attention on the four areas in which the largest numbers of animals suffer the most intensely for the longest periods of time: in the food industry, in the clothing trade, in laboratories, and in the entertainment industry. PETA works through public education, cruelty investigations, research, animal rescue, legislation, special events, celebrity involvement, and protest campaigns. https://www.peta.org

[i] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Killer_whale

[ii] https://www.npr.org/sections/13.7/2012/09/11/160934187/for-how-long-have-we-been-human

[iii] http://newsroom.ucla.edu/releases/ucla-biologists-report-how-whales-159231

[iv] http://www.dailygalaxy.com/my_weblog/2010/06/whale-evolution-a-snapshot-of-planet-earth-from-55-million-bc-to-present.html

[v] https://www.orcanetwork.org/Main/index.php?categories_file=Natural%20History%20of%20Orcas%20-%20Part%201

[vi] http://us.whales.org/wdc-in-action/meet-different-types-of-orca

[vii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Killer_whale

[viii] https://www.thestranger.com/books/feature/2015/08/05/22646533/orcas-have-ruled-the-planet-longer-than-we-have-and-theyre-smarter-than-we-know

[ix] https://www.orcanetwork.org/Main/index.php?categories_file=Births%20and%20Deaths

[x] https://www.thestranger.com/books/feature/2015/08/05/22646533/orcas-have-ruled-the-planet-longer-than-we-have-and-theyre-smarter-than-we-know

[xi] https://www.thestranger.com/books/feature/2015/08/05/22646533/orcas-have-ruled-the-planet-longer-than-we-have-and-theyre-smarter-than-we-know

[xii] https://www.thestranger.com/books/feature/2015/08/05/22646533/orcas-have-ruled-the-planet-longer-than-we-have-and-theyre-smarter-than-we-know

[xiii] https://www.thestranger.com/books/feature/2015/08/05/22646533/orcas-have-ruled-the-planet-longer-than-we-have-and-theyre-smarter-than-we-know

[xiv] https://www.peta.org/features/wild-captured-orcas-make-legal-history/

[xv] https://www.seaworldofhurt.com/features/court-case-seaworld/

[xvi] http://www.blackfishmovie.com/about

[xvii] http://time.com/3987998/seaworlds-profits-drop-84-after-blackfish-documentary/

[xviii] https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation-now/2014/03/07/san-diego-seaworld-orca-shows/6162331/

[xix] https://www.cnbc.com/2017/01/07/seaworld-san-diego-ending-killer-whale-shows.htm

Earth Law for Angoon, Alaska

The Native Tnglit people of Southeastern Alaska depends on local ecosystems for their diets and livelihoods. They have created a coalition to protect their environment from damage by commercial activity.

By Jaishal Dhimar

For thousands of years, civilizations have organically spurred up near water sources. Of course any civilization near a water source gains use of easy to access shipping routes, but even today with our multitude of planes and highways for ground transport, we humans continue to find the coast home. 39% of the world’s population currently live directly on the shoreline.

As the world’s coastlines recede due to the devastating effects of global warming we see an increase in people living closer to the coastline. Naturally, seafood production and consumption has increased.

The Native Tnglit people of Alaska, whose name translates to “People of The Tides” have called the Southeastern Alaskan shoreline home for thousands of years. Much of their diet consists of local seafood and other native species. As stated in my last blog, much of coastal land was or is owned by private companies.

The Tnglit people are facing an issue from the Green Creaks Mining company. Green Creaks is encroaching on natural land in Hawk Inlet by infesting it with their dumping. This infected water disturbs local fauna, and creatures as far as sixty miles away in Angoon, where a large Tnglit population resides. As coastlines recede more of the dangerous minerals from the mining company is breaching further away from it’s dumping site. We have to re examine policy to keep up with changing environmental systems.

Source: University of Alaska www.uaf.edu/anla/collections/map/

What is Angoon/Hawk Inlet?

Hawk Inlet is a beautiful port considered to be apart of Juneau, Alaska. Hawk Inlet is a key part of Juneau, as not only is it a port, but also used as a nearby airport, and apart of the Admiralty mining district. Hawk Inlet has been a key part of infrastructure for Alaska’s capital, Juneau, for over one hundred years. Without this key district, much of Alaska’s economy would be in shambles, as the mining district is the 5th highest producer of silver in the world, and a huge producer of other materials as well.

Source: John Cobb Field Handbook(University of Washington) content.lib.washington.edu/cobbwebb/index.html

Hawk Inlet has been a port since 1908.

There is one allowed discharger of materials in Hawk Inlet and that is Green Creeks Mine operated by Hecla Green Creeks Mining Company. Green Creaks had an ore spill in 1989 and studies show that there is three times as much mercury in local shellfish, and sediment compared to the rest of the state of Alaska. Many of these creatures travel downstream, and are consumed by seal and other species, who have been found with excess mercury in their systems.

For reference, fish do often naturally have small amounts of mercury in their system as the Earth’s crust creates mercury organically. However, Alaskan native species are often found to have very little to no mercury in their system. The Green Creeks Mining company is seeking to expand.

Angoon is a gorgeous natural habitat and has the highest density of brown bears and bald eagles in the world. About sixty miles downstream from Hawk Inlet, it is off the beaten trail, Rarely visited by tourists, especially compared to Juneau, but Angoon is home to some of the coastal Tlingit people. Angoon is in protected territory, in the center of the Tongass National forest that could possibly be adversely affected by the pollution coming off from Hawk Inlet.

Figure 1 Source: Carl Chapman "Driving to Alaska" flickr.com/photos/12138336@NO2/1953213698/

The small city of Angoon

The mine is an important economic factor from the mines to Juneau, but the people of Angoon are being directly impacted as well as other people ingesting some of the local seafood. This is only a small fraction of the problem as not only is Hawk Inlet affecting local areas, other mines near Juneau are flowing into tributaries near the Taku River, close to Juneau. Many of these mining companies decide to leak material into the rivers and dealing with the light consequences later. Comments have been made about the Tulsequah Chief Mine, that while the government requests the mining companies clean up their mess, the mining companies either account for the fines and continue to do what they were doing previously, or ignore the requests completely.

Day Trip to Angoon Joseph/Umnak http://www.flickr.com/photos/umnak/

What’s Being Done?

The Tlingit people and other tribes banded together to create a coalition to tackle these problems that impact indigenous people’s way of life. The Angoon Community Association, tackles the various issues that prevent Angoon citizens from having say in issues related to their home and surrounding area, along with being a bastion for community outreach.

I want to thank “Di-kee aan kaawoo” which translates to “Our heavenly Father” for the opportunity to take care of the resource. A quote by Frank Jack, Sr., Tlingit Bear Chief and House Master of the Shanaax Hit (Valley House) of Angoon, Alaska.

The association have multiple demands, including but not limited to,

Indigenous peoples have the right to the full enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms;

Indigenous peoples have the right to participate in decision-making in matters which would affect their rights, through representatives chosen by themselves in accordance with their own procedures, as well as to maintain and develop their own indigenous decision making institutions;

States shall consult and cooperate in good faith with the indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free, prior and informed consent before adopting and implementing legislative or administrative measures that may affect them;

Indigenous peoples have the right, without discrimination, to the improvement of their economic and social conditions, including, health;

Indigenous peoples have the right to their traditional medicines and to maintain their health practices, including the conservation of their vital medicinal plants, animals and Minerals;

Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain and strengthen their distinctive spiritual relationship with their traditionally owned or otherwise occupied and used lands, territories, waters and coastal seas and other resources and to uphold their responsibilities to future generations in this regard;

States shall establish and implement a transparent process to recognize and adjudicate the rights of indigenous peoples pertaining to their lands, territories and Resources;

Indigenous peoples have the right to redress for the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned or otherwise occupied or used, and which have been confiscated, taken, occupied, used or damaged without their free, prior and informed consent;

Indigenous peoples have the right to the conservation and protection of the environment and the productive capacity of their lands or territories and resources; and

Indigenous peoples have the right to determine and develop priorities and strategies for the development or use of their lands or territories and other resources.

In short, the people of indigenous demand retribution for not only themselves, but the land that has been abused, ask for representation in future projects relating to their territory or resource, and have the right to their traditional culture.

What Would Earth Law Look Like For Angoon?

Option 1: Amendment of Angoon Community Association Constitution

ELC can assist in drafting amendments to the “Constitution and By-laws of the Angoon Community Association Alaska.” Ratified in 1939, the law can be amended to adapt to the present times and to provide a stronger foundation to protect indigenous and nature’s rights. ELC partners Movement Rights and CELDF have helped the Ho-Chunk Nation and Ponca Nation amend their constitution to include rights of nature. On October 20th 2017, the Ponca Tribe of Oklahoma took the historic step of agreeing to add a statute to enact the Rights of Nature.

Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin general council voted to add “rights of nature” to tribal constitution 2016. The amendment establishes: “Ecosystems and natural communities within the Ho-Chunk territory possess an inherent, fundamental and inalienable right to exist and thrive.” Further it prohibits frac sand mining, fossil fuel extraction, and genetic engineering as violations of the Rights of Nature.

Option 2: Pass a Sustainability Rights Ordinance for Angoon

ELC can assist in drafting a local law that can address the issues Angoon faces. Particularly, the law may include the right of Angoon’s community to self-governance, to a healthy environment and to defend and enforce the rights of nature and other applicable laws. This can also include specific provisions referring to restoration of Hawk Inlet, practices regarding the mine and gray water discharge, and stricter implementation of the CWA.

Option 3: Treaty Agreement for legal rights for the Hawk Inlet and/or Chatham Straits

ELC can assist in drafting a treaty agreement between the Angoon Community Association and the State or Federal government. The agreement would include declaring the ecosystems as legal entities. The agreement would also create new standard procedures for decisions, all must go through a designated Board, to be comprised of both Angoon community members and state/federal persons to ensure all decisions serve the interests of the ecosystem.

In 2013, the Tūhoe people and the New Zealand government agreed upon the Te Urewera Act, giving the Te Urewera National Park “all the rights, powers, duties, and liabilities of a legal person.”

A Board was then established to serve as “guardians” of Te Urewera and to protect its interests. The stated purpose of the Act was to protect Te Urewera “for its intrinsic worth,” including its biodiversity and indigenous ecological systems.

As a result, the government gave up ownership of Te Urewera, and all decisions must serve the interests of and preserve the relationship of the Te Urewera and the Tuhoe people. From a legal standpoint, this legislation is monumental. There is no longer a requirement to demonstrate personal injury in order to protect the land; lawsuits “can be brought on behalf of the land itself.”

Similarly, the Maori people have successfully pursued similar results for the Whanganui River and its tributaries, under the Maori worldview “I am the River and the River is me.” Under the Tutohu Whakatupua Treaty Agreement, the river is given legal status under the name Te Awa Tupua . Te Awa Tupua is recognized as “an indivisible and living whole” and “declared to be a legal person.”

Two guardians, one from the Crown and one from a Whanganui River iwi, will be given the role of protecting the river.

Additionally, these agreements have come with apologies from the Crown and payment in damages caused. In the case of the Whanganui River a “financial redress of NZ$80m is included in the settlement, as well as an additional NZ$1m contribution towards establishing the legal framework for the river.

In essence, the government has allowed mining companies to decide what actions they want to take. Whether that is half way cleaning up long lasting damage, or deciding to dump in new territories, there is little substantial action taken that deters companies from moving forward with long set plans.

If Earth Law is bestowed upon the Association’s land, this will allow for higher levels of protection for all the surrounding ecosystem, animals, and the humans to allow for prosperity across generations rather than the short-lived mine that only benefits the corporation.

How you can help

Check us out at www.earthlawcenter.org to keep updated on how Earth Law Center is working to transform the law to recognize and protect nature’s inherent rights to exist, thrive, and evolve.

Stay informed and sign up for our newsletter

Become a volunteer with ELC

Donate to the initiative

My previous blog about Louisiana Wetlands.

https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2016/07/14/bp-deepwater-horizon-costs/87087056/

http://dhss.alaska.gov/dph/Epi/eph/Documents/DHSS_DEC_2016-02-29_Angoon%20Response.pdf

http://juneauempire.com/local/2017-04-27/angoon-seal-hunters-still-solving-mercury-mystery

https://ourworldindata.org/meat-and-seafood-production-consumption

content.lib.washington.edu/cobbwebb/index.html

www.uaf.edu/anla/collections/map/

Rights of Nature to Save the Endangered Sharks of the Galapagos

Threats facing sharks in the Galápagos Islands, and the Earth Law solutions that can help protect them.

Hammerhead shark Vlad Karpinskiy @Creative Commons

By Shelia Hu and Michelle Bender

The Galápagos Islands are a haven for sharks

With 34 of the globe’s 440 known species, the Galapagos Islands have the highest abundance of sharks in the world.[1]

A UNESCO World Heritage center, the Galapagos lies about 1,000 kilometers from the Ecuadorian Coast. Three major tectonic plates —Nazca, Cocos and Pacific— meet here. The ongoing seismic and volcanic activity create a truly unique ecosystem. The Galapagos achieved fame in scientific circles when Charles Darwin published the “Voyage of the Beagle” in 1839.[2]

The Galápagos Marine Reserve is one of the largest marine reserves in the world, covering a total area of 130,000 square kilometers of Pacific Ocean and featuring a dynamic mix of tropical and Antarctic currents and rich areas of upwelling water.

Consequently, the Galapagos Marine Reserve (GMR) contains an extraordinary range of biological communities, hosting such diverse organisms as penguins, fur seals, tropical corals, and large schools of hammerhead sharks. The GMR has a high proportion of endemic marine species – between 10% and 30% in most taxonomic groups – and supports the coastal wildlife of the terrestrial Galapagos National Park (GNP). It also appears to play an important role in the migratory routes of pelagic organisms such as marine turtles, cetaceans and the world’s largest fish, the whale shark (Rhincodon typus).[3]

In 2016, the President of Ecuador, Rafael Correa, announced the creation of a new marine sanctuary to protect the water around the Galapagos Islands. The sanctuary is designed to fall around the islands of Darwin and Wolf in order to protect the world’s greatest concentration of sharks.[4]

The area will include 39,000 square kilometers within the Galapagos Marine Reserve, an area in which industrial fishing has been banned since 1998 but where smaller fishing operations are allowed.[5] The new shark sanctuary will mean several areas within the GMR will be designated as “no-take” zones where no fishing of any kind will be allowed. The sanctuary will protect around 32% of waters surrounding the Galapagos, with no fishing activity, mining, or oil drilling allowed at all.[6]

The extra step of protection is needed as the ecosystem faces the increased stressors of climate change, industrial trawlers, and illegal fishing.

Whale Shark Vlad Karpinkskiy @Creative Commons

The mystery of the pregnant whale sharks

The largest fish in the ocean, the whale shark eats plankton and other small fish – collected as the whale shark swims. Preferring warm waters, whale sharks populate all tropical seas. They are known to migrate every spring to the continental shelf of the central west coast of Australia. The coral spawning of the area's Ningaloo Reef provides the whale shark with an abundant supply of plankton.[7]

There isn’t much else known about this type of shark and its social habits. They haven’t been studied as well as other sea creatures, according to the IUCN.[8]

The whale sharks in the Galapagos Marine Reserve, unlike elsewhere, tend to be large mature females (99.8%), and over 90% appear to be pregnant.[9] To find out more about why these pregnant whales stopover at the Galapagos (but with no sign of newborns), the Galapagos Whale Shark Project launched. After tracking it was found that Darwin island provides an important point for navigation for the sharks, on their way to feeding grounds in the Pacific Ocean.[10]

Hammerhead nursery found in Galápagos waters

A nursery for scalloped hammerhead sharks was recently discovered along the coast of the Santa Cruz Island in the Galapagos, good news for better understanding and protecting an endangered species.[11]

Their wide-set eyes give them a better visual range than most other sharks. And by spreading their highly specialized sensory organs over their wide, mallet-shaped heads, they can more thoroughly scan the ocean for food. One group of sensory organs is the ampullae of Lorenzini. It allows sharks to detect, among other things, the electrical fields created by prey animals. The hammerheads’ increased ampullae sensitivity allows them to find their favorite meal, stingrays, which usually bury themselves under the sand.[12]

After a nine to ten month gestation, scalloped hammerhead sharks give birth to their pups who can then slowly mature into adulthood in the well-protected, food-rich environment safe from many of their natural predators (like other sharks) in the open ocean. [13]

Threats facing sharks in Galápagos waters

Sharks are under serious threat around the globe. It is estimated that up to 70 million sharks are killed by people every year, due to both commercial and recreational fishing. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has classified 64 of the 440 shark species as endangered, and one-third at risk of extinction, according to its 'Red List' criteria.[14] Sharks are caught intentionally or as accidental "by-catch" in virtually all types of fisheries worldwide.[15]

Most sharks are long-living species that grow slowly, mature late, and have low reproduction rates. These biological factors make sharks particularly vulnerable to overfishing and mean that populations can be slow to recover once depleted. The continuous depletion and even eradication of these top predators in the structure of many marine habitats will have catastrophic consequences for ecosystems such as coral reefs and may cause the extinction of many other interdependent species.[16]

While sharks in Galapagos are protected by the Galapagos Marine Reserve, they roam quite far and can be affected by illegal fishing and bycatch in fisheries targeted at other species.[17]

Over 6,600 dead sharks, mostly hammerheads but also silky, thresher and mako sharks— which are off-limits to industrial fishers within the marine reserve — were found on an unauthorized ship in the Galapagos Reserve in August 2017. An Ecuadorean judge has since convicted the ship's 20 crew members of possessing and transporting protected species. In addition to prison sentences, the ruling also fined them $5.9 million.

"The sentence marks a milestone in regional environmental law and an opportunity to survive for migratory species," the country's Ministry of Environment said in a statement. This case also marked the first conviction of an environmental crime in 14 years of Galapagos law and set a precedent for prosecuting shark finning and other crimes against nature in the Galapagos (Franco Fernando, 2015).

Isla de San Cristobal, Diego Delsa

Ecuador, a world leader in Rights of Nature

In 2008, Ecuador became the first country to adopt Rights of Nature into its Constitution. The Constitution, endows “Nature or Pachamama, where life is reproduced and exists” with inalienable rights to “exist, persist, maintain and regenerate its vital cycles, structure, functions and its processes in evolution.”

The Constitution also gives nature the right to restoration and the people the right to “live in a healthy and ecologically balanced environment that guarantees sustainability and the good way of living.” It is the responsibility of the Ecuadorian State to “respect the rights of nature, preserve a healthy environment and use natural resources rationally, sustainably and durably” and to provide incentives to the citizens to “protect nature and to promote respect for all the elements comprising an ecosystem.”[18]

Ocean Rights can help the sharks of the Galapagos

Earth Law Center is working with local partners through the Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature to ensure the constitutional amendment is implemented with respect to ocean governance.

Implementing ocean rights and expanding protection of the Galapagos, will also help Ecuador achieve its goals within the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and United Nations Sustainable Development goals; including expanding marine protected areas to 8170 square kilometers.[19]

The Marine Reserve represents the beginning of the desire to apply rights of nature to ocean protection. The Special Law of the Galapagos’s guiding principle for governance is ‘‘An equilibrium among the society, the economy, and nature; cautionary measures to limit risks; respect for the rights of nature; restoration in cases of damage; and citizen participation.” However, in order to ensure activities within the Reserve respect the rights of nature, there needs to be legally binding provisions that do so within the management plan.

One way to implement the rights of nature in the Galapagos, is to pass a decree declaring the Reserve (and proposed Sanctuary) as a legal entity, subject to basic rights. Defining in law the Reserve as a legal entity recognizes the area as a living whole, and legally requires that the State protects the rights of the ecosystem and species within.

Similarly the management plan must explicitly define the highest objective for management as conserving the Reserve in as close to its natural state as possible. Protecting and restoring the ecosystem for its own benefit can occur only if conservation objectives are prioritized over human-centered objectives, such as economic development. Secondary objectives can include tourism, fisheries, recreation, education and scientific research, but these must also be explicitly defined as secondary objectives.

In countries, such as New Zealand, guardians are being appointed on the management boards for the protected area that represent the ecosystem’s interests and ensures it’s rights are not being violated; they will review decisions, monitor compliance and develop new rules to protect the Reserve. Such an approach can also work in Ecuador, allowing the guardians to use their standing to bring legal action upon parties involved with activities directly affecting the health and well-being of the Reserve.

Finally, management must fully take into account all species interactions and land-based activities. In order to manage human activity holistically within the Reserve, criteria must be developed to ensure activities respect the rights of nature. Such criteria can include:

- Reflecting on the true cost of our activities and their impacts, which includes costs to the marine ecosystem and its ability to renew and restore itself.

- Evaluate decisions using attributes and scores that assign the highest scores to those activities and regulations that lead to the fulfillment of the conservation objectives.

- Application of the Precautionary Principle which puts the burden of proof on those wishing to take potentially harmful action – to prevent harm before it occurs.

- Development of alternative livelihoods that allow for both human and ecological interests to thrive. Key considerations for Earth-Law centered ecological criteria may include:

- Impacts to keystone species, such as sharks, are given priority in decision making.

The Earth Law Framework for Marine Protected Areas further outlines how rights of nature can be implemented in the Galapagos Marine Reserve. Employing this framework will help Ecuador implement rights of nature throughout their oceanscape.

Act today and join the growing global movement of Earth Law by:

More about Global Alliance for Rights of Nature (GARN)

The Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature (the “Alliance”) is a network of organizations and individuals committed to the universal adoption and implementation of legal systems that recognize, respect and enforce “Rights of Nature” and to making the idea of Rights of Nature an idea whose time has come. Find out more at http://therightsofnature.org/

[1] https://galapagosconservation.org.uk/sharks-galapagos-islands/; https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/mar/21/ecuador-creates-galapagos-marine-sanctuary-to-protect-sharks

[2] https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1

[3] https://www.galapagoswhaleshark.org/the-project/why-study-whale-sharks/

[4] “Ecuador creates new marine sanctuary to protect sharks”, 21 March 2016, Galapagos Conservancy, https://www.galapagos.org/newsroom/new-marine-sanctuary/ Accessed: 7 June 2018

[5] “Ecuador creates new marine sanctuary to protect sharks”, 21 March 2016, Galapagos Conservancy, https://www.galapagos.org/newsroom/new-marine-sanctuary/ Accessed: 7 June 2018

[6] Ibid.

[7] https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/fish/w/whale-shark/

[8] https://www.livescience.com/55412-whale-sharks.html

[9] https://galapagosconservation.org.uk/projects/whale-shark-monitoring/

[10] https://www.galapagoswhaleshark.org/the-project/what-we-discovered-so-far/

[11] https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2018/01/hammerhead-shark-nursery-discovery-galapagos-spd/

[12] https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/fish/group/hammerhead-sharks/

[13] https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2018/01/hammerhead-shark-nursery-discovery-galapagos-spd/

[14] https://www.theguardian.com/science/2009/jun/25/sharks-extinction-iucn-red-list

[15] http://sharksmou.org/threats-to-sharks

[16] http://sharksmou.org/threats-to-sharks

[17] https://galapagosconservation.org.uk/sharks-galapagos-islands/

[18] Republic of Ecuador, Constitution of 2008, available at: http://pdba.georgetown.edu/Constitutions/Ecuador/englis h08.html.

[19] Ibid.

Earth Law Ocean Framework Launches!

Current methods for protecting Earth’s oceans fall short in many ways. Learn how the holistic, systems and rights-based approach outlined by the Earth Law Ocean Framework addresses the threats facing Earth’s oceans.

By Kaitlyn O’Halloran

Michelle Bender, Ocean Rights Manager at Earth Law Center, unveiled the final Earth Law Framework for Marine Protected Areas at the Ocean Conference at EARTHx on Earth Day 2018.

Building on past and current protections, this Earth Law Framework adopts a holistic, systems and rights-based approach to governance. This ocean framework provides guidance to countries establishing marine protected areas.

As commercial fishing stocks run decline and images of the Great Pacific Plastic patch spread over the media, we are all looking for ways to protect the ocean — which covers 70% of the planet we call home.

How is this different from existing ocean protections?

Rather than looking at the ocean as a limitless resource, the Framework considers the ocean as a fellow subject — that is, an entity with a legal right to exist, thrive and evolve.

The ocean rights framework specifically calls for:

the legal recognition of marine protected areas;

the legal recognition of the rights of and values associated with marine protected areas;

the appointment of guardians to represent marine protected areas’ interests;

the right for humans to speak on behalf of marine protected area in legal matters;

the application of legal rights in the existing governance system.

Only 4% of the ocean remains undamaged by human activity

The scale and inaccessibility of oceans means that we have better maps of Mars than the ocean [1]. The “out of sight, out of mind” syndrome comes into play, since if we don’t know what damage has been done, it’s the same as no damage at all.

Ten years ago, an international team of scientists led by Dr Benjamin Halpern of the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis in Santa Barbara, USA, developed the first detailed global map of human impacts on the seas, using a sophisticated model to handle huge amounts of data. The team divided the world’s oceans into square kilometer sections and combined data for each section on 17 different human impacts to oceans, including fishing, coastal development, fertilizer runoff, and pollution from shipping traffic [2].

Their findings showed that just 4% of the world’s oceans remain undamaged by human activity. Climate change, fishing, pollution, and other human activities have taken their toll in some way on all the other 96% of the world’s oceans. 41% of the oceans are seriously damaged [3].

Research says fish are sentient

According to the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA), fish are sentient animals who form friendships, experience “positive emotions” and have individual personalities. The RSPCA published a landmark new study which found zebrafish are social animals in a similar way to humans and other mammals [4].

Fish can also reason their way through a space-time puzzle designed by humans. Cleaner wrasse chose between eating from two plates: one blue, one red. If they started with the red, the blue plate stayed and they could have both. If they started with the blue, then the red plate was removed. Elsewhere, similar experiments have been done with three species of intelligent primates: eight capuchin monkeys, four orangutans, and four chimpanzees.

The fish solved the problem better than any of the primates. Of the six adult cleaner wrasses tested, all six learned to eat from the red plate first. It took them around 45 trials to figure it out. In contrast, only two of the chimpanzees solved the problem in less than 100 trials (60 and 70, respectively). The remaining two chimps, and all of the orangutans and monkeys, failed the test. The test was then revised to help the primates learn, and all of the capuchins and three of the orangs got it within 100 trials. The other two chimps never did [5].

By way of comparison, one of the study’s authors, Redouan Bshary, tried the test on his four-year-old daughter. After one hundred trials she had not learned to eat from the red plate first [6].

What difference will Earth Law make?

There are many practical and immediate ways that Earth Law can strengthen and accelerate efforts to protect and restore ocean health.

Earth Law will require regulations to regulate harmful human activities from land. For plastic pollution for example, plastic manufacturing, handling, and transportation facilities could be required to implement minimum best management practices (BMPs) to control discharge and a 1mm mesh screen installed downstream from all preproduction plastic locations.

Reduce carbon dioxide emissions. For instance by driving the transition to renewable energy, and decreasing subsidies to the fossil fuel industry.

Reduce fishing pressures to levels that allow the fish populations to naturally regenerate themselves to as close to the natural carrying capacity of the ecosystem as possible. This includes the establishment of no-take zones, stricter quotas, seasonal closures etc.

Earth Law also places the burden of proof on those wishing to undertake the extractive activity. They must show that the activity will not violate the MPA’s rights (compared to the current situation where defenders of ocean health bear the burden of proof and must prove to a court of law that the proposed activities will harm ocean health before legal action can be taken). The different roles for humans in Earth Law include the following:

Guardians for the ocean can participate in any legal process affecting the ecosystem (particularly “appearing before national legislative and rule-making bodies to help clarify ocean impacts of proposed actions”), develop or review any relevant guidelines, monitor the health of the MPA [marine protected area], monitor compliance with applicable laws and treaties, and represent the ecosystem in disputes. The guardians have “standing” on behalf of the marine protected area.

Citizens can seek injunctive relief from harmful activities such as oil spills, overfishing, plastic pollution etc. not only for funds to be applied toward restoration but for a change in behavior. Required injunctive relief could be stricter fishing quotas or moratoriums on taking species if the level or way of hunting is violating the species’ rights.

Local communities can fulfill their collective responsibility and press for government action if a protected area is not being implemented, reducing the phenomenon of paper parks.

Earth Law Framework already at work

Organización para la Conservación de Cetáceos (OCC), a small non-government organization in Uruguay, focuses on marine conservation. In 2013, a delegation of primary and secondary students led by OCC met face-to-face with parliamentarians to designate Uruguay’s territorial sea as a sanctuary for Whales and Dolphins.

Uruguay adopted law 19.128 in September 2013, prohibiting the chasing, hunting, catching, fishing, or subjecting of cetaceans to any process by which they are affected or harmed.

Thirty-one species of cetaceans, either resident or migratory, exist within the Sanctuary, including the Southern Right Whale and the endangered La Plata Dolphin. In this region, the convergence of two major ocean currents, the Rio de la Plata estuary, “and the relatively shallow waters of the area, combine to produce a singular hydrographic system.” This creates one of the “most productive aquatic systems in the world, used by many demersal fish for spawning and nursing and sustains several artisanal and industrial fisheries [7].”

Earth Law Center is partnering with OCC to establish legal rights for Uruguay’s Whale and Dolphin Sanctuary. Designating the Sanctuary as a legal entity subject to basic rights will:

Require the government to support the creation of a management plan for the Sanctuary

Require the State to protect, restore, and maintain the health of the Sanctuary, namely through the establishment and implementation of marine protected areas

Help the country reach the SDG and CBD AICHI targets — 10% of national waters protected by 2020

Regulating tourism and shipping traffic to have minimal effect on cetaceans in the Sanctuary

Prohibiting extraction, seismic exploration, offshore drilling and deep sea mining in critical areas

Achievements include promoting a decree for responsible whale watching (261/02), promoting the installation of viewing platforms along the coast and establishing protocols of good marine practice and certification.

Next steps include:

Submit a proposal to Parliament to designate legal rights for the Sanctuary through a legal decree

Draft the management plan for the Sanctuary informed by ELC’s model MPA framework and coordinated with the National System of Protected Areas

Plan participatory meetings in each community, including technicians in fisheries and marine management

We have submitted a Hope Spot application to Mission Blue to amplify awareness and impact of campaign. A decision should be made by the Sanctuary's fifth anniversary in September 2018.

Ocean conservation organizations worldwide are supporting the Earth Law Framework. In fact, the framework has spurred conversations and partnerships in over 35 countries. We all agree that our approach needs to change, and that we must respect and protect the ocean. Earth Law provides the way to implement this change and respect for life.

Conclusion

Let’s work together to reverse the decline of ocean health before it is too late.

Our actions add up. The state of Hawaii recognizes this by becoming the first state to ban sunscreens which contain oxybenzone and octinoxate (present in about 60% of commercial sunscreens today). Scientists have found that these chemicals contribute to coral bleaching. An estimated 14,000 tons of sunscreen is believed to be deposited in the ocean annually, with the greatest damage found in popular reef areas in Hawaii and the Caribbean [8]. Taking effect in 2021, the law helps nudge manufacturers to do what they have thus far been unwilling to do – make a reef safe sunscreen.

We are at a critical juncture in human history, we have the unique opportunity to help protect and restore ocean health. Here is a framework that provides a tangible and innovative solution. Let’s work together to protect our oceans both now and for future generations.

How Can You Help?

To ensure the ocean’s health and future for many years to come, we must take advantage of this opportunity to change the way the ocean is treated. There are various ways in which you can help protect the oceans and support the Framework for Marine Protected Areas:

We can enforce the Earth Law Framework for Marine Protected Areas by establishing legal standing for the oceans. Read the framework here.

We can work on local levels to ensure that the rights of the ocean are being acknowledged and protected. Launch a local initiative here.

We can ensure that the inherent rights of the ocean are made known to the public and legislators alike, to promote the Earth Law Framework so its guidelines are efficiently enforced. Volunteer with Earth Law Center here.

We can encourage our representatives to implement the guiding principles of the Earth Law Framework when making decisions which affect the ocean’s health. Donate here.

We can continue to become more informed citizens, focusing on efforts to further protect the ocean and its inherent rights. Sign up for the Earth Law Center Newsletter here.

1. https://www.nasa.gov/audience/forstudents/5-8/features/oceans-the-great-unknown-58.html

2. http://oceanleadership.org/state-of-our-oceans/

3. http://oceanleadership.org/state-of-our-oceans/

5. http://nautil.us/issue/40/learning/fish-can-be-smarter-than-primates

6. What a Fish Knows by Jonathan Balcombe p.128

7. Miloslavich P, Klein E, Díaz JM, et al. Marine Biodiversity in the Atlantic and Pacific Coasts of South America: Knowledge and Gaps. Thrush S, ed. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(1):e14631. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014631.

8. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/03/travel/hawaii-sunscreen-ban.html

An Earth Law Solution to Ocean Plastic Pollution

Plastic pollution in Earth's oceans seriously threatens marine ecosystem health; current environmental laws have failed to address this global issue.

By Michelle Bender

Photo by Michelle Bender