Earth Law Center Blog

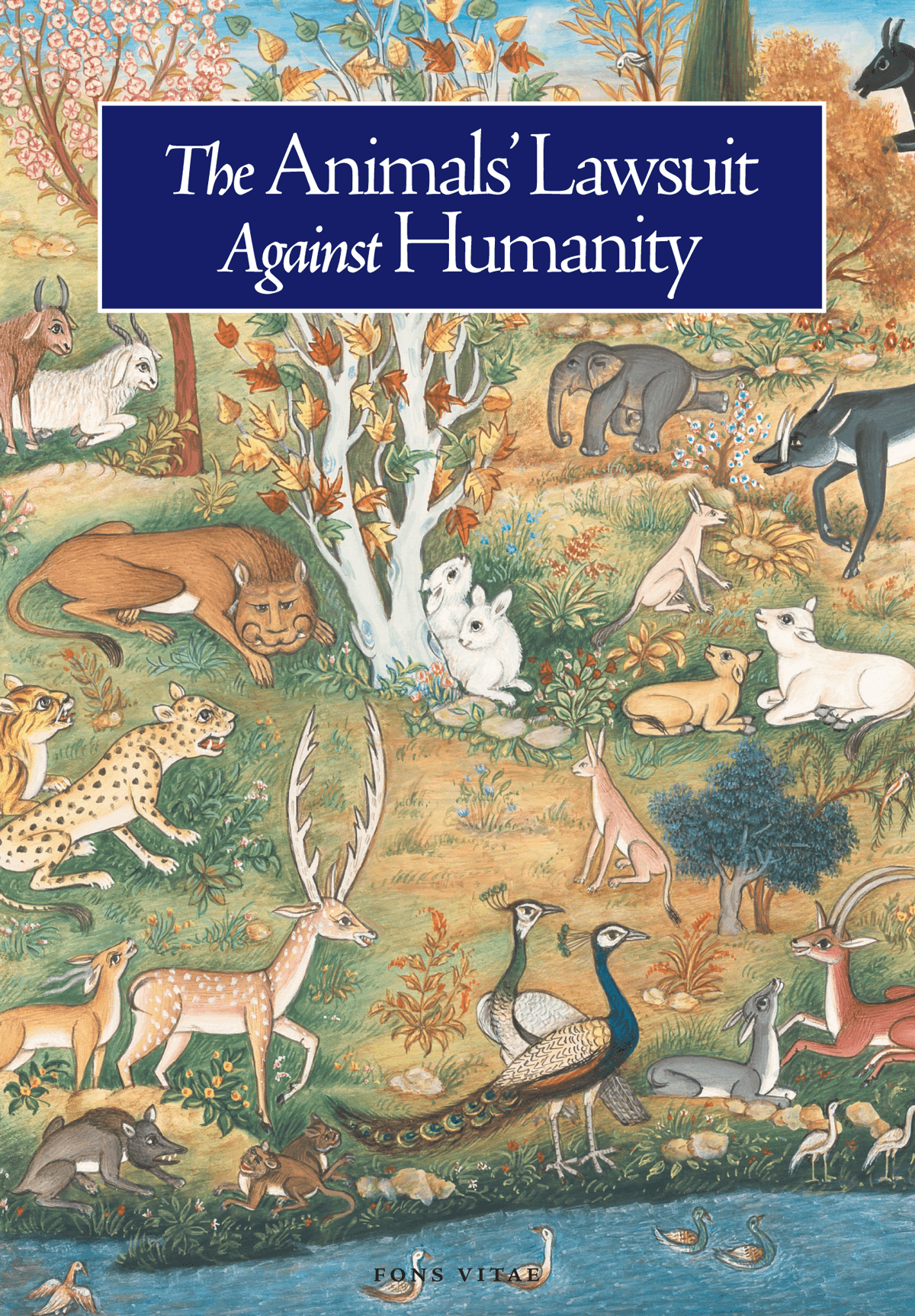

An Interview with Rabbi Anson Laytner, Translator of "The Animals' Lawsuit Against Humanity"

In this interfaith and multicultural fable, eloquent representatives of all members of the animal kingdom—from horses to bees—come before the respected Spirit King to complain of the dreadful treatment they have suffered at the hands of humankind. During the ensuing trial, where both humans and animals testify before the King, both sides argue their points ingeniously, deftly illustrating the validity of both sides of the ecology debate.

Meet Carla Cardenas—Environmental & Forest Expert for ELC

Carla Cardenas is an integral part of the Earth Law Center’s environmental & forest policy. Read up on her unique journey!