In Landmark Opinion, Inter-American Court of Human Rights Recognizes Rights of Nature

Logo of the IACtHR

By Aitana Rosas Linhard and Earth Law Center

On July 3, 2025, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR) issued its historic Advisory Opinion OC-32/25, declaring that the climate crisis has escalated into a “climate emergency” and affirming for the first time that States have clear obligations under human rights law to confront it. The opinion also marked the first time an international court has formally recognized Nature as a subject of rights.

Just weeks after the IACtHR issued its opinion, the UN’s International Court of Justice (ICJ) released its own advisory opinion about climate change. The request, brought forward by a group led by the small Pacific island nation of Vanuatu, was for the Court to define States’ obligations to prevent climate change. In response, the ICJ declared that climate change is an “existential threat”—similar to the IACtHR’s declaration of a “climate emergency”—and affirmed that States’ failures to take action to protect the climate system could be violations of international law.

July 2025 thus saw two major supranational courts release landmark opinions that signal meaningful progress in mobilizing international law to confront the climate crisis. And the IACtHR went a step further by explicitly recognizing the Rights of Nature, marking a significant development in ecocentric jurisprudence.

In this blog post, we explore the IACtHR’s recognition of the Rights of Nature (including pertinent excerpts from the opinion), the Court’s role in international law, the key 2017 precedent it set building to this recent advisory opinion, and how its landmark incorporation of the Rights of Nature might influence future decisions by States and other courts. (For more on the ICJ ruling, check out this Inside Climate News article.)

Rights of Nature in the IACtHR advisory opinion

The IACtHR’s advisory opinion came in response to a joint request from Chile and Colombia, two countries increasingly vulnerable to the devastating effects of climate change, including floods, droughts, landslides, and fires. Their request sought legal clarity on States’ responsibilities in confronting these escalating ecological threats.

The opinion, spanning over 200 pages, sets out a detailed interpretation of States’ legal duties to prevent, mitigate, and address the impacts of climate change. Grounding the protection of the environment in States’ legal responsibility to protect the rights of their inhabitants, the opinion frames the climate crisis in part as a human rights obligation rather than merely an issue of politics and policy. Drawing on principles of international human rights law, it synthesizes legal principles with fundamental human rights, integrating concepts such as sustainable development and planetary boundaries, and, for the first time, affirming the Rights of Nature.

Here are the critical excerpts (Section B.1.2. and paragraph 315) from the body of the opinion that address Earth jurisprudence and the Rights of Nature—citations are here omitted, please visit the original opinion to see them for greater understanding of the Court’s sources.

THE COURT . . . IS OF THE OPINION

By a vote of four in favour and three against, that:

7. The recognition of Nature and its components as subjects of rights is a normative development that reinforces the protection of the integrity and functionality of ecosystems in the long term, providing effective legal tools in the face of the triple global crisis and facilitating the prevention of existential damage before it becomes irreversible. This conception represents a contemporary manifestation of the principle of interdependence between human rights and the environment, and reflects a growing trend at the international level to strengthen the protection of ecological systems from present and future threats, in accordance with paragraphs 279-286.

. . .

B.1.2. The protection of Nature as a subject of rights

279. Ecosystems are complex and interdependent systems, in which each component plays an essential role for the stability and continuity of the whole. Degradation or alteration of these elements can cause cascading negative effects that affect both other species and humans as part of these systems. Recognition of Nature's right to maintain its essential ecological processes contributes to the consolidation of a truly sustainable development model that respects planetary boundaries and ensures the availability of vital resources for present and future generations. Moving towards a paradigm that recognises the rights of ecosystems is essential for the long-term protection of their integrity and functionality, and provides coherent and effective legal tools in the face of the triple planetary crisis to prevent existential damage before it becomes irreversible.

280. This recognition makes it possible to overcome inherited legal conceptions that conceived of nature exclusively as an object of property or an exploitable resource. Recognising nature as a subject of rights also implies making visible its structural role in the vital balance of the conditions that make the habitability of the planet possible. This approach strengthens a paradigm centred on protecting the ecological conditions essential for life and empowers local communities and indigenous peoples, who have historically been the guardians of ecosystems and possess deep traditional knowledge about their functioning.

281. The Court further emphasizes that this approach is fully compatible with the general obligations to adopt domestic law provisions (Article 2 common to the American Convention and the Protocol of San Salvador), as well as with the principle of progressivity that governs the realization of economic, social, cultural and environmental rights (Article 26 of the Convention and Article 2 of the Protocol of San Salvador). Indeed, the protection of Nature, as a collective subject of public interest, provides an enabling framework for States - and other relevant actors - to advance in the construction of a global normative system oriented towards sustainable development. Such a system is essential to preserve the conditions that sustain life on the planet and to ensure a dignified and healthy environment, indispensable for the realisation of human rights. This understanding is consistent with a harmonious interpretation of the pro-nature and pro-person principles.

282. Likewise, the Court recalls that, according to Article 29 of the American Convention, the interpretation of the rights protected in the inter-American system must be guided by an evolutionary perspective, in line with the progressive development of international human rights law. In this sense, the recognition of Nature as a subject of rights does not introduce a content alien to the inter-American corpus iuris, but rather represents a contemporary manifestation of the principle of interdependence between human rights and the environment. This interpretation is also in line with advances in international environmental law, which has affirmed structural principles such as intergenerational equity, the precautionary principle and the duty of prevention, all of which are aimed at preserving the integrity of ecosystems in the face of current and future threats.

283. From this understanding, the Court underlines that States must not only refrain from acting in ways that cause significant environmental harm, but have a positive obligation to adopt measures to ensure the protection, restoration and regeneration of ecosystems (infra paras. 364-367 and 559). These measures must be consistent with the best available science and recognise the value of traditional, local and indigenous knowledge. They must also be guided by the principle of non-retrogression and ensure full procedural rights (supra para. 240 and infra paras. 468, 478 and 480).

284. The Court highlights the efforts made at the international level to promote an inclusive approach to the protection of nature. In this regard, it notes that the 1982 World Charter for Nature affirms that "[t]he human species is part of nature and life depends on the uninterrupted functioning of natural systems which are a source of energy and nutritive materials", and that "[e]very form of life is unique and deserves to be respected, whatever its usefulness to man and in order to recognise the intrinsic value of other living beings, man must be guided by a code of moral action". This instrument also states that "[n]ature shall be respected and its essential processes shall not be disturbed". For its part, the Convention on Biological Diversity recognises in its preamble the "intrinsic value of biological diversity and the ecological, genetic, social, economic, scientific, educational, cultural, recreational and aesthetic values of biological diversity and its components". Further to this Convention, the Kunming-Montreal Global Framework for Biological Diversity states that "[b]oth nature and nature's contributions to people are essential to human existence and a good quality of life [. . .]". Likewise, the Court underlines that the Agreement on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity in Areas beyond National Jurisdiction has as one of its purposes to ensure "the sound management of the ocean in areas beyond national jurisdiction, on behalf of present and future generations [. . .] conserving the inherent value of biological diversity".

285. This Court notes the adoption by the United Nations General Assembly of fifteen resolutions and thirteen reports evidencing the growing recognition of Earth jurisprudence and the rights of Nature at the global level. Complementarily, the Compact for the Future adopted by UN Member States in 2024 declares "the urgent need for a fundamental change in [their] approach in order to achieve a world in which humanity lives in harmony with nature".

286. Finally, the Court observes a growing normative and jurisprudential trend that recognises Nature as a subject of rights. This trend is reflected in judicial decisions at the regional and global levels, as well as in the domestic legal systems of various countries in the Americas, such as Canada, Ecuador, in some states of the United States of America, Bolivia, Brazil, Mexico, Panama, and Peru.

. . .

315. Thus understood, the right to a healthy climate projects its effectiveness not only on current and future generations of human beings, but also on Nature, as the physical and biological sustenance of life. The protection of the global climate system requires safeguarding the integrity of ecosystems and the living and non-living components that make up and sustain them. In turn, the preservation of climatic conditions compatible with life is essential to maintain the balance and functionality of these ecosystems. This reciprocal interdependence between climate stability and ecological balance reinforces the need for an integrative legal approach, capable of articulating the protection of human rights and the rights of Nature in a normative framework consistent with the harmonious interpretation of the pro persona and pro natura principles (supra para. 281).

Nestled within an opinion concerned with tackling the climate crisis, this fulsome recognition of the Rights of Nature is a notable victory for the Earth law movement.

Before further exploring this opinion, including how it attempts to balance the right to development, other human rights, and the Rights of Nature, we next look at the place the IACtHR holds in international human rights jurisprudence as well as the key precedent on which this new advisory opinion builds.

What is the Inter-American Court of Human Rights?

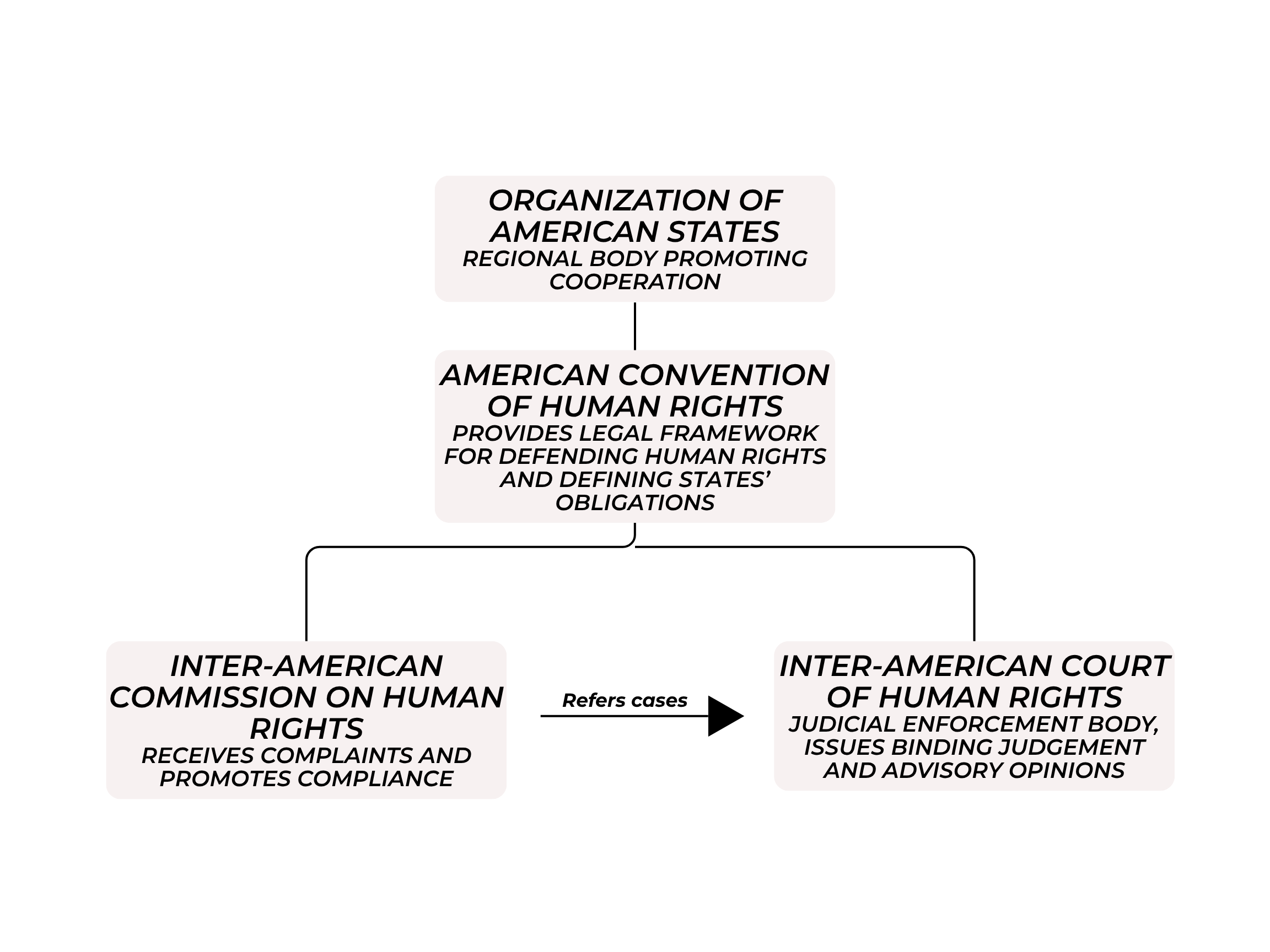

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights (the Court) is one of the world’s three major regional human rights tribunals, alongside the European and African human rights courts. Based in San José, Costa Rica, it serves as the judicial organ of the Organization of American States (OAS), a regional body founded in 1948 to promote peace, justice, and cooperation across the Americas.

The Court, together with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, is tasked with ensuring State compliance with the American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR), also known as the Pact of San José. As stated in its preamble, the ACHR was created “to consolidate in this hemisphere, within the framework of democratic institutions, a system of personal liberty and social justice based on respect for the essential rights of man.” This foundational treaty commits States to respect, protect, and fulfill a wide range of civil, political, social, and cultural rights.

Graphic by Aitana Rosas Linhard

Members of the IACtHR. Dark red – accept blanket jurisdiction of the court. Orange – signatories not accepting full jurisdiction. Yellow – former members.

By Kwamikagami - File:World blank map countries.PNG, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=70104222

The Court exercises contentious (dispute-resolving) and precautionary (preventive) powers. Yet it is a third category of issuances, its non-binding advisory opinions, that have in particular become powerful tools for legal innovation. These opinions guide national courts, lawmakers, and civil society in advancing rights-based approaches to urgent regional and global challenges, including climate change. The Court has exercised significant influence on the application and implementation of constitutional law across Latin America, particularly through its progressive interpretation of the ACHR.

The 2025 opinion’s key precedent: IACtHR Advisory Opinion OC-23/17

The Court is no stranger to addressing environmental issues from a human rights perspective. In 2017, it issued Advisory Opinion OC-23/17, a foundational decision that laid the groundwork for an evolving climate jurisprudence. The opinion, requested by Colombia, concerned how new infrastructure projects would negatively affect the marine environment of the wider Caribbean Region, and, by extension, human life. Colombia also asked the Court for clarification regarding how the ACHR should be interpreted in conjunction with other environmental treaties, such as the Convention for the Protection and Development of the Marine Environment in the Wider Caribbean Region.

Although the request stemmed from Colombia’s location-specific concern, the Court broadened its interpretation, acknowledging that environmental degradation poses a serious threat to the rights of individuals everywhere.

The ruling reads, in part:

“The Court considers it important to stress that, as an autonomous right, the right to a healthy environment, unlike other rights, protects the components of the environment, such as forests, rivers and seas, as legal interests in themselves, even in the absence of the certainty or evidence of a risk to individuals. This means that it protects nature and the environment, not only because of the benefits they provide to humanity or the effects that their degradation may have on other human rights, such as health, life or personal integrity, but because of their importance to the other living organisms with which we share the planet that also merit protection in their own right. In this regard, the Court notes a tendency, not only in court judgments, but also in Constitutions, to recognize legal personality and, consequently, rights to nature . . . .

Furthermore, in the specific case of indigenous and tribal communities, the Court has ruled on the obligation to protect their ancestral territories owing to the relationship that such lands have with their cultural identity, a fundamental human right of a collective nature that must be respected in a multicultural, pluralist and democratic society.”

OC-23/17 thus became one of the Court’s first explicit assertions that States have human rights obligations to prevent environmental harm. Specifically, it recognized the human right to a healthy environment and presaged its future support for the Rights of Nature. The advisory opinion established a range of obligations States have to ensure within and beyond their territory, including:

Regulating, supervising, and monitoring activities within their jurisdiction that could cause significant environmental harm

Conducting environmental impact assessments when projects pose a significant risk of environmental harm to ecosystems or communities

Preparing contingency plans to minimize the likelihood of major environmental accidents and mitigate any damage

Mitigating existing environmental damage

Acting in accordance with the precautionary principle by protecting the rights to life and personal integrity, regardless of the existence scientific certainty that there is a plausible risk of serious harm

Cooperating in good faith with other States to ensure protection against significant transboundary harm to environments

Notifying other potentially affected States about planned activities that could result in transboundary harm

Ensuring the right to public participation in decision-making, and the right of access to justice in environmental matters.

In this progressive advisory opinion, the Court affirmed that Nature holds intrinsic value independent of its utility to human beings. Although the opinion’s language left the Court at one remove from fully endorsing Rights of Nature (“the Court notes a tendency . . . to recognize legal personality and, consequently, rights to nature” [emphasis added]), it nevertheless has served as a key endorsement for the Rights of Nature movement, providing judges, lawyers, and advocates with a highly relevant legal instrument to promote progressive interpretations in the region’s courts. These include the recognition of the Rights of Nature and the effective application of principles such as precaution and prevention.

Did the 2017 advisory opinion inspire real change in subsequent cases?

In a landmark 2020 decision in Indigenous Communities of the Lhaka Honhat (Our Land) Association v. Argentina, the IACtHR held that Argentina had violated several interdependent rights of Indigenous communities, including their rights to a healthy environment, community property, cultural identity, food, and water. It was the first time in a contentious case that the Court recognized these rights autonomously under Article 26 of the American Convention, which obliges States to progressively realize economic, social, and cultural rights. Drawing heavily from its earlier Advisory Opinion OC-23/17, the Court established that the right to a healthy environment protects ecosystems such as forests and rivers not only for their utility to humans but also as entities of intrinsic value. The Court ordered Argentina to adopt specific reparations, including access to food and water, recovery of forest resources, and restoration of Indigenous cultural practices.

Another concrete example is the 2024 ruling that recognizes the Marañón River (Peru) as a subject of rights. In that case, the Peruvian court explicitly invoked Advisory Opinion OC-23/17 as part of its legal reasoning, reaffirming the decisive impact of the Court’s interpretation of the ACHR.

Ultimately, Colombia’s request for Advisory Opinion OC-23/17, which initially concerned local marine development and the obligations of the State to confront climate change, was successful in advancing its own environmental jurisprudence. In Future Generations v. Ministry of the Environment and Others, the Colombian Supreme Court recognized the Colombian Amazon as a subject of rights. A group of youth plaintiffs argued that State inaction on deforestation and climate change violated their constitutional rights to a healthy environment. Drawing on reasoning set forward in the 2017 Advisory Opinion, the Court ordered the government to implement short, medium, and long-term action plans to protect the Amazon, and to create an “Intergenerational Pact for the Life of the Colombian Amazon” in consultation with affected communities, climate scientists, research groups, and plaintiffs. However, the pact has yet to be created, and efforts to do so appear to be stalled.

Despite the important precedent set by the 2017 advisory opinion, the intervening years have made it clear that even stronger measures and more expansive legal frameworks are needed to address the climate emergency. Recognizing the right to a healthy environment is an increasingly popular legal strategy, as evidenced by the rise of “Green Amendments” in state constitutions across the United States and the ICJ’s recent advisory opinion. However, recognizing this critical and fundamental right may not be sufficient in the face of escalating ecological collapse. The continued inability of anthropocentric legal frameworks to adequately address planetary environmental crises has contributed to the developmental momentum of alternative ecocentric approaches.

The IACtHR’s 2025 advisory opinion reflects this shift from a focus on environmental protection for the sake of humans to the protection of Nature for its intrinsic value. Though the opinion also retains language on people’s economic rights, it affirms Nature as worthy of legal protection to a degree never before seen by an international court.

Rights of Nature in the context of the 2025 advisory opinion

Requested by Chile and Colombia, the Court’s 2025 advisory opinion regarding climate change emerges in a time of intensifying global climate pressures. As record-breaking floods sweep through unprepared regions, and rising temperatures spike heat-related death tolls, many people—and especially high percentages of youth—are terrified of what the future holds. Humans feel their fundamental right to a healthy environment has been violated and that the biosphere itself is a victim of unprecedented risks. In such a context, what difference will the IACtHR opinion make?

In their joint request, Chile and Colombia asked the Court to clarify how the ACHR obliges member States to respond to climate change. Framing climate change as a threat to fundamental human rights, the opinion outlines States’ obligations to mitigate GHG emissions, regulate corporate activities, create climate impact assessments for proposed projects, and actively work to protect ecosystems.

The prevailing issue addressed in the opinion is the climate emergency, which the Court situates within the context of the “triple planetary crisis” of climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss. It outlines the causes of climate change and its current and potential impacts, assesses international responses, and explores related domestic regulatory developments in OAS member States. A significant portion of the text aims to resolve why the current context should be understood as a “climate emergency” requiring immediate action.

In addition to recognizing that environmental degradation constitutes a violation of human rights, the Court affirms the human right to “participate in, contribute to and enjoy development” (paragraphs 211, 243, 370). It clarifies that such development must be sustainable, defined by a balance between the social dimension, economic growth, and environmental protection.

Notably, the Court frames both the right to a healthy environment and the right to development as fundamental. Yet in practice, these rights often stand in opposition. Development has historically come at the expense of wild ecosystems, and environmental protection is frequently sidelined in the name of economic progress. By affirming both as fundamental rights, the Court mandates States to reconcile economic development with the protection of Nature under a unified legal framework. Its direct affirmation of the Rights of Nature helps give greater credence to Nature as part of this balance, suggesting a reimagining of what development means in the face of the climate emergency.

The opinion’s recognition of the intrinsic legal value of ecosystems opens the door to increased recognition of the autonomy of rivers, forests, and other natural entities.

As seen in the excerpts above, the Court notes the UN General Assembly’s growing attention to and interest in the Rights of Nature, observes its growth as a “normative and jurisprudential trend” at the regional and global levels and in domestic legal systems. It articulates that the interests of humans and the interests of Nature must now be reconciled within a unified legal framework. Though the tension is not yet resolved, the advisory opinion legally recognizes the necessity of this integration.

The IACtHR’s explicit recognition of the Rights of Nature will hopefully stimulate the creation of an adequate legal framework in which a stable global climate system, thriving ecosystems, humans' right to a healthy environment, and development in harmony with nature can each be achieved. The Court stressed the need for a sustainable development model, as defined by the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, where human activity is harmonious with the ecological limitations of the planet. Following this claim, the Court writes, “This requires adopting a systemic and integrating perspective, which is seen as an essential element for the protection of the right to a healthy climate” (paragraph 316).

While sustainable development has often been framed in terms of balancing economic growth with responsible resource use, an ecocentric legal approach brings a concurring perspective that reinterprets development through the lens of Nature’s intrinsic value. Rather than standing in opposition, ecocentric law can serve as a complementary framework that ensures the voices of Nature are included in legal and policy decisions. Instruments like the Sustainable Development Goals and the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework reflect this synthesis, pointing toward a future in which development is redefined in alignment with both human rights and the Rights of Nature.

Conclusion

The IACtHR’s 2025 advisory opinion on climate change builds on a legal path first illuminated in 2018, when the Colombia Amazon ruling first linked the Rights of Nature to climate litigation. Since then, ecocentric principles have emerged as powerful tools to confront environmental collapse. This new judgment affirms that without a transformative paradigm shift—one that places Nature at the center—States will fail to meet their climate obligations.

The Rights of Nature are essential not only in defining the substantive duties of States but also in ensuring the procedural mechanisms required to address the global environmental emergency. Thus, by recognizing the Rights of Nature in addition to the right to healthy climate, the opinion compels States to take specific action to protect the climate system and ecosystems. By holding governments accountable for protecting the rights of their inhabitants, human and non-human, the IACtHR’s advisory opinion offers us an important guide in the face of the triple planetary crisis.